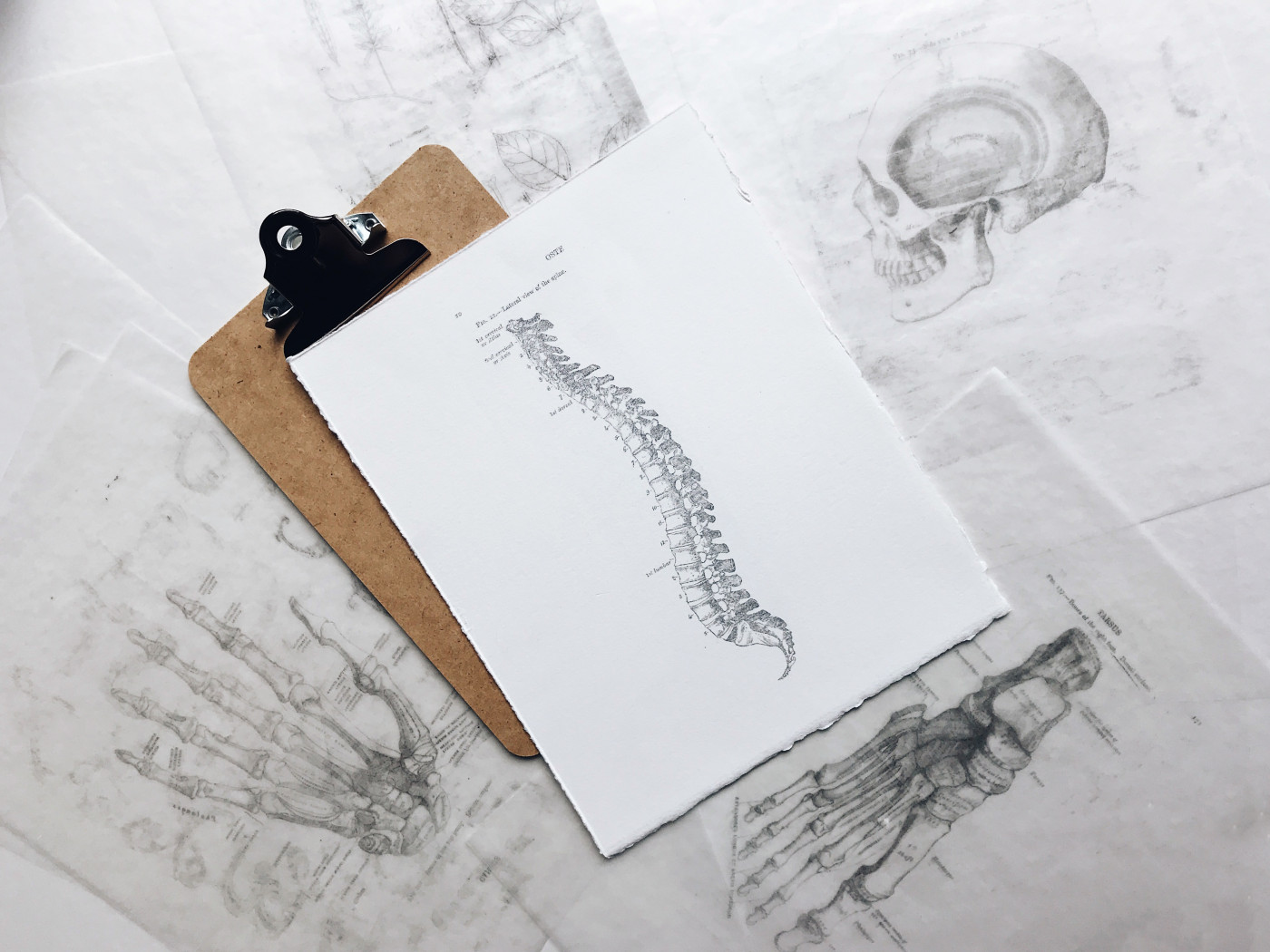

Delivering Spinraza to Patients with ‘Complex Spines’ Possible Using Different Puncture Route, Study Says

Photo by Joyce McCown on Unsplash

An alternative form of intrathecal (via the spinal canal) injection, called a transforaminal puncture, is a safe and effective way of delivering Spinraza (nusinersen) to spinal muscular atrophy patients whose scoliosis makes standard spinal injections difficult, according to real-world data from the Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

The study, “The Complex Spine in Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Transforaminal Approach—A Transformative Technique,” was published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology.

The loss of motor neurons that marks SMA leads to progressive muscle weakness, including in areas around the spine. This frequently causes deformities, such as the sideways curvature of the spine known as scoliosis.

Depending on its severity and how quickly the curvature worsens, SMA patients may need surgery to stabilize their spine, like spinal fusion that permanently connects two or more vertebrae or the use of rods.

Prior to injections of Spinraza — the first disease-modifying SMA treatment, developed by Biogen, and one approved for all patient groups and ages — considerations of spinal anatomy are essential because of its intrathecal route of delivery. That is, the therapy is injected directly into the spinal canal, and after an initial “induction phase” is given once every four months.

Ask questions and share your knowledge of Spinal Muscular Atrophy in our forums.

Typically, intrathecal delivery is done by interlaminar lumbar punctures, or an injection into the lower spine (lumbar area). But this approach may not be feasible in complex conditions like fusion or rods, because they can interfere with the needle’s path.

Physicians and researchers at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, for this reason, group SMA patients being treated with Spinraza at their center by whether they have “simple” or “complex” spines, rather than by SMA type (i.e., SMA 0–4) or age.

The team reviewed 164 Spinraza injections given to 31 patients with types 1-3 (ages 4 months to 18 years) between March 2017 and September 2018. Nine of these patients had complex spines.

Their study describes initial experiences giving repeated treatments to these nine people using two alternative types of intrathecal delivery — transforaminal lumbar punctures (TF) and cervical punctures, or injections into the upper spine (cervical, or neck, area).

These two techniques target different areas of the spine: while a cervical puncture’s entry site is between vertebrae C1 and C2 and targets the spinal cord and the spinal laminar line, a transforaminal lumbar puncture targets the lower half of the spine in an area called the neural foraminal space. The spine’s foramen is the gaps or openings between vertebrae through which spinal nerve roots travel, exiting to other parts of the body.

Both approaches require imaging exams prior to the injection (called preprocedural imaging), and initial needle guidance via CT scans or X-rays while the injection is being delivered. All such injections were performed at Phoenix Children’s under general anesthesia.

A total of 45 Spinraza injections were given these nine complex spinal patients (mean age, 14.5 years) during the study’s period, 42 by transforaminal lumbar puncture and three by cervical puncture. These three cervical procedures were the first alternative spinal injection method tried by the doctors, who came to favor transforaminal lumbar puncture as they gained experience in using it because of its lower risk.

In all patients, injections were 100% successful and without complications, the researchers reported, adding they thought preprocedural imaging essential to that success rate. The mean “room time” for all procedures was 50 minutes and 18 seconds.

“In our practice, the first option is the TF [transforaminal] approach with cervical approaches considered if the TF approach fails,” the researchers wrote. “Although cervical approaches were successful without complications, the TF approach is preferred because of the lower risk profile and the extended fluoroscopy times encountered with the cervical routes.”

Their experiences, the researchers added, “has resulted in a protocol-driven approach based on simple or complex spinal anatomy. Patients with simple spines do not need preprocedural imaging or imaging-guided intrathecal nusinersen injections.”

The complex spine group, however, “requires preprocedural imaging for route planning and imaging guidance for therapy, with the primary approach being the transforaminal approach for intrathecal nusinersen injections,” they concluded.