Swallowing problems in SMA may be declining since advent of DMTs

Studies show improved, stabilized function since treatments became available

Written by |

Swallowing function may have improved in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patients since disease-modifying therapies (DMT) have become available, a review study suggests.

The analysis showed problems with swallowing were prevalent in the years before the emergence of DMTs and that studies after the treatments became available indicated stabilizations or improvements.

Still, a lack of standardized assessment tools made it difficult to compare findings from different studies or to pinpoint a specific therapy with the most benefits.

“Future research should prioritize identifying optimal therapies for individual swallowing function and develop validated assessments to optimize SMA management,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Swallowing function in patients with spinal muscular atrophy before and after the introduction of new gene-based therapies: what has changed?,” was published in Neurological Sciences.

In SMA, nerve cells involved in muscle control begin to degenerate, leading to progressive muscle weakness and wasting.

The muscles involved in chewing and swallowing can also become affected, leading to swallowing dysfunction, called dysphagia, that increases the risk of choking and makes it harder to get adequate nutrition. Swallowing and feeding problems are especially prominent in SMA type 1, a severe form of the disease that emerges in infancy.

Over the last decade, three DMTs have been approved for treating SMA — Evrysdi (risdiplam), Spinraza (nusinersen), and Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) — which work in different ways to boost production of the SMN protein that SMA patients lack.

Evidence for improved swallowing in SMA

Having these treatment options has drastically improved outcomes for SMA patients. However, most studies have focused on motor outcomes and survival, meaning there’s not as much information about how swallowing function has changed for SMA patients in the DMT era.

Here, scientists in Italy reviewed 23 published studies that evaluated swallowing function in SMA patients between 2004 and 2024, a time period that spans the pre- and post-DMT eras. Nine studies were conducted in untreated patients, and 14 were in the treated group. Only one study in the pre-DMT group included SMA type 1 patients, while six in the post-DMT group did. This was because, before DMTS were available, most studies focused on less severe SMA types because type 1 patients often had a breathing tube implanted (tracheostomy), the use of which has decreased in recent years.

Swallowing problems were frequently reported across SMA types in the pre-DMT studies. Patients most commonly recalled problems with chewing, choking on solids and liquids, and abnormal tongue movements during eating. They often needed multiple attempts to clear their mouths when swallowing.

The one pre-DMT study with SMA type 1 patients found that patients usually required a feeding tube by around age 6 months due to significant swallowing problems.

Studies in the post-treatment era “demonstrated a potential shift in swallowing function,” the researchers wrote. Most of these studies reported trends toward improved or stabilized swallowing with treatment, including in patients who previously required a feeding tube.

Need for standardized assessments

Not having a standardized assessment tools across the studies made it difficult to compare outcomes, however, the researchers said.

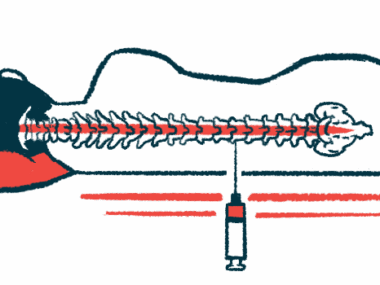

Studies before DMTs often relied on subjective measures like caregiver-completed questionnaires. This shifted substantially in studies involving treated patients, where video fluoroscopy, an X-ray based procedure that lets doctors visualize what happens during swallowing, became the predominant method for monitoring swallowing.

“This shift highlights a trend towards greater objectivity and reliability in the outcome measures employed,” the researchers wrote.

More recently, scientists have developed tools to specifically look at swallowing in SMA patients. Validating and implementing such tools will help optimize patient care, the researchers said.

There’s not enough evidence so far to suggest if there is a particular therapy that’s best for improving swallowing function.

“Direct comparisons of these therapies’ impact on swallowing function are challenging, but crucial for future studies to optimize clinical practice,” the researchers wrote. “This will allow determining which therapy offers the greatest benefit for swallowing, ultimately supporting more individualized treatment decisions.”