Uplifting Athletes Tackles Funding for Rare Disease Research, Awareness

Written by |

Photo courtesy of Uplifting Athletes

Garrett Hopkin, a boy with Niemann-Pick disease types A and B, meets Ryan Bates, left, offensive lineman for the Bills, and quarterback Josh Allen, right

Football and science seem to be disparate fields of play at first glance, but the nonprofit Uplifting Athletes is finding common ground by leveraging the popularity of college gridiron games to fund research for rare diseases.

Its nearly two dozen chapters — representing college football teams across the nation — are organizing fundraisers to help young researchers find treatments for the approximately 7,000 known rare diseases.

Rob Long, executive director of Uplifting Athletes, attends the Global Genes’ 8th Annual RARE Champions of Hope Celebration at Sheraton San Diego and Marina on September 20, 2019. (Photo by Mike McGinnis/Getty Images)

“We can really generate genuine awareness for the rare disease community through the platform of athletics,” Robert Long, the executive director of Uplifting Athletes, said in a video interview.

“We have so many people that support us solely based on the sports aspect of what we do and that provides us the opportunity to educate them about the needs of the rare disease community,” said Long, a former Syracuse punter who had his career cut short because of a rare brain cancer.

In the past three years, Uplifting Athletes has awarded $440,000 in grants to more than 20 scientists as part of its Young Investigator Draft, which is modeled after the NFL Draft for professional football teams in the U.S. This draft selects investigators from the U.S. and Canada in the early stages of their research careers who are working on rare diseases.

A patient advocacy group nominates an eligible researcher, and the scientific advisory council then grades each investigator according to a rubric that focuses on project feasibility and the relevant education and training of the applicant. The impact the research will make in the rare disease community also is a key focus. Awards will go to the top applicants, the number of which depends on available funding.

Applications for 2o22 are now open; the deadline to apply is Nov. 18, and winners will be announced by the end of the year. The grant is for one year, with a minimum award of $20,000, half of which is funded by Uplifting Athletes and the other half by the nominating group.

The 2021 “draft class” included research focusing on diseases such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, blinding retinal diseases, and DDX3X syndrome, a recently discovered neurodegenerative disorder that typically occurs in females and is associated with developmental delays and autism spectrum disorder.

Uplifting Athletes also makes an effort to include researchers from diverse backgrounds as part of its Underrepresented Researchers in Medicine initiative, which began in 2020. Through this program, the advisory council ensures at least one project from underrepresented researchers is selected.

“What we’re trying to accomplish is creating more diversity and equity in the research space, and providing opportunities to researchers from underrepresented backgrounds to be celebrated amongst their peers through the investigator draft,” Long said.

Garrett Hopkin, a boy with Niemann-Pick disease types A and B, meets with Buffalo Bills quarterback Josh Allen. (Photo courtesy of Uplifting Athletes)

Uplifting Athletes was started in 2003 after former Penn State football player Scott Shirley’s father was diagnosed with kidney cancer, which is classified as a rare disease by the National Institutes of Health because it affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

To raise money for research into rare cancers, Shirley and his Penn State teammates opened their summer weight training to the public; they called it Lift for Life and raised $13,000 as a result. The next year, they raised $38,000.

Uplifting Athlete’s primary funding source comes from its chapters, which host events on campus, such as Lift for Life, now the oldest program of the nonprofit.

Until 2015, each college campus was responsible for working with a patient advocacy organization for a specific rare disease. The University of Washington football team, for example, had started its chapter to raise money and awareness for pediatric multiple sclerosis, since the father of one of the team’s offensive linemen had the adult form of the disease.

As the organization grew larger, however, it was difficult for Long and his small team of employees to stay on top of relationships with more than 20 nonprofits. He also found it made it difficult to stay on message with a broad mission of serving all rare diseases.

So, the Uplifting Athlete chapters now pool their monies together to support the larger organization and the scientists in the Young Investigator Draft.

“That was a more impactful way to utilize the funding and support where we could point specifically to the researchers and the research that we were funding, as opposed to just passing it through for different organizations and different amounts,” Long said.

Uplifting Athletes is using the millions of eyes that watch college football to their advantage by bringing awareness to the underrepresented rare disease community.

Players at participating universities wear patches on their uniforms during spring games. During the season, some will paste Uplifting Athletes stickers on their helmets.

Awareness also has been spread as some of the players go into the NFL. A dozen players sport custom Uplifting Athletes cleats every December as part of the NFL’s My Cause My Cleats campaign, which allows players to support charities by wearing unique cleat designs.

The “Uplifting” part of the organization’s name refers to the collegiate players as well, as the nonprofit helps its student-athletes learn leadership skills after they finish their amateur or professional careers.

For the past 13 years, Uplifting Athletes has held a leadership conference for chapter leaders. According to Long, the goal is to help student-athletes first understand the goals and mission of the organization and, secondly, coach them in life and leadership skills to prepare them for when they eventually hang their helmets up.

“As a Division 1 football player, you don’t have the opportunity to work a full-time job or to do an internship,” Long said. “We provide that through uplifting athletes and try to help the athletes become the best version of themselves as they can be.”

Every year for the past 12 years, the organization has honored a Rare Disease Champion — any leader in college football who has helped the rare disease community.

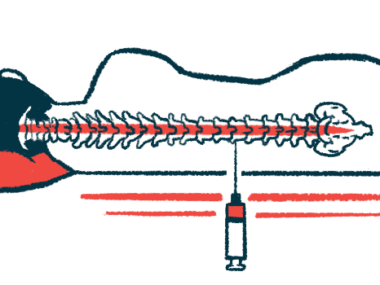

Before COVID-19, part of the Uplifting Athletes’ mission was to connect rare disease families with the football players for whom they are rooting. Every summer before the pandemic, the entire Notre Dame college football team met with rare disease patients for a night of bowling. Last July, Garrett Hopkin, a boy with Niemann-Pick disease types A and B, got to meet Josh Allen, quarterback for the Buffalo Bills pro football team.

Long himself was impacted by Uplifting Athletes in 2012 after players started a chapter at Syracuse University, in New York, focused on brain cancer research in his honor.

At the end of his senior year as a punter, in December 2010, doctors discovered a large tumor in his brain that would require immediate surgery. He was later diagnosed with grade 3 anaplastic astrocytoma, a rare type of brain cancer.

Even though Long would eventually recover, after a long and difficult treatment cycle, his hopes to play in the NFL were dashed. Yet he still had a successful college punting career, and in 2016, he became the director of rare disease engagement at Uplifting Athletes, and eventually the organization’s executive director.

“I wanted to take what I’ve experienced and what I’ve lived through and use that as a way to kind of pay it forward,” Long said. “That’s when I got involved with Uplifting Athletes.”