Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type I: SMA2 Gene May Determine Severity

Written by |

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University Medical Center in New York have studied the characteristics of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type I in five infants with the disorder in a study titled Spectrum of neuropathophysiology in spinal muscular atrophy type I published in the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. The two most severely affected infants had a single copy of the SMN2 gene, while less affected individuals had two copies, suggesting that absence of the SMN2 gene negatively impacts this disorder.

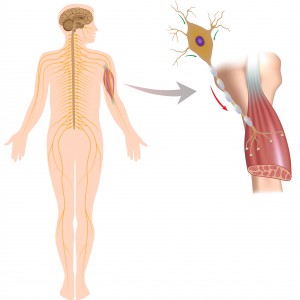

SMA is a genetically determined neuromuscular disorder characterized by loss of specific spinal cord neurons, which causes weakness of the limbs and muscle degeneration. This leads to loss of voluntary muscle movement. SMA is most commonly caused by a mutation of the SMN1 gene on chromosome 5. The age of SMA onset, symptoms and rate of progression varies — the younger the onset, the more severe the symptoms. SMA is classified into types 1 through 4 to account for the variability in symptoms and onset age.

SMA is a genetically determined neuromuscular disorder characterized by loss of specific spinal cord neurons, which causes weakness of the limbs and muscle degeneration. This leads to loss of voluntary muscle movement. SMA is most commonly caused by a mutation of the SMN1 gene on chromosome 5. The age of SMA onset, symptoms and rate of progression varies — the younger the onset, the more severe the symptoms. SMA is classified into types 1 through 4 to account for the variability in symptoms and onset age.

SMN stands for “survival motor neuron protein.” This protein, as its name implies, helps protect the nerve cells that process movement, particularly in the spinal cord. Most of the functional SMN in the body is made by the SMN1 gene. A smaller amount of SMN protein is made from a gene similar to SMN1 called SMN2. Because the SMN1 gene is typically defective in SMA, the SMN2 gene could compensate for this problem, by creating some SMN protein.

The researchers, led by Brian Harding of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, examined five infants, post-mortem, for different clinical characteristics of SMA. They measured compound motor action potential amplitude, which is a way of determining how well nerve cells are conducting impulses. They also measured the number of SMN2 gene copies as well as different brain regions that process movement.

[adrotate group=”3″]

The researchers found that the “2 clinically most severely affected patients had a single copy of the SMN2 gene.” They also found nerve cell (neuron) death in many brain and spinal cord regions that process movement. Less severe SMA cases had 2 copies of the SMN2 gene and did not have as severe brain and spinal cord damage.

The scientists concluded, “We present a pathophysiologic model for SMA-I as a protein deficiency disease affecting a neuronal network with variable clinical thresholds. Because new treatment strategies improve survival of infants with SMA-I, a better understanding of these factors will guide future treatments.”

Based on this study, it appears that the number of SMN2 gene copies could impact how severe SMA-I becomes. This may indicate a protective effect of the SMN2 gene and the protein that it produces. However, studies in larger groups of individuals would help to confirm this study. The SMN2 gene could provide a target in addition to the SMN1 gene, for the eventual treatment of this disease.