SMA Expert Arthur Burghes, Speaking in Poland, Urges Universal Newborn Screening

Written by |

Underscoring the enormous progress researchers have made understanding spinal muscular atrophy, Dr. Arthur Burghes called for newborn screening for the incurable degenerative disease and the urgent approval of new therapies for it.

Burghes’ remarks came in a keynote lecture at today’s start of the International Scientific Congress on Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Kraków, Poland. The Jan. 25-27 event is the first in Europe dedicated specifically to the disorder, which occurs in roughly one in every 10,000 births.

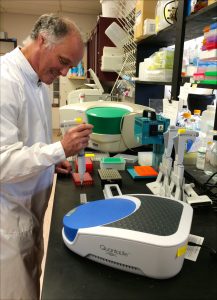

Burghes, a professor of biological chemistry and pharmacology at Ohio State University College of Medicine, spoke on the subject “Where Have We Come, Where Do We Go?” The SMA expert, who has a PhD from the University of London and did post-doctoral work at the University of Toronto, has spent 30 years studying the disorder.

“During the time I’ve been researching SMA, we’ve gone from not knowing the gene [underlying the condition], to identifying the gene, to having mice models of the disease, to having large animal models, to actually having therapies,” Burghes told SMA News Today in phone interview Jan. 18 from his lab in Columbus, Ohio. “When those therapeutics are given early in the disease course or even before symptoms occur, they have a major effect on the progression of the disease.”

EU Approval of Spinraza a Turning Point

The conference that Burghes and 400 other SMA experts are attending comes six months after the European Union approved Biogen’s Spinraza (nusinersen) for SMA types 1, 2 and 3.

Type 1, the most severe form of the disease, is usually diagnosed at birth or within the first six months of life. It is caused by mutations of the SMN1 gene that lead to a shortage of the survival motor neuron, or SMN, protein. Spinraza works by altering SMN2, a gene nearly identical to SMN1 that in healthy people generates only a small amount of SMN. The drug’s aim is to cause SMN2 to produce enough functional SMN protein to increase the survival of motor neurons, nerve cells that control movement.

“What pathway is critical for the destruction of motor neurons, or is it a combination of pathways with SMN functioning? What do those pathways each contribute?” Burghes asked. “We don’t really know the answers to these questions, but what’s critical in answering them is to have suppressors that suppress each of those specific pathways and have them tested in mice, so we can learn how the actual biochemistry of the disease works.”

He added that “there are definitely modifiers of the SMA phenotype. Can these modifiers be identified and used in combination with therapies already out there? We don’t know.”

More Approved Therapies Bring Prices Down

Spinraza, which is delivered by injection, has a list price of $125,000 per dose, so the first year’s six injections cost $750,000. This makes it one of the world’s most expensive medications.

Last August, Switzerland’s Roche began enrolling infants with SMA type 1 in a Phase 2 study of RO7034067, a therapy that targets SMN2. The move came after positive early results in a similar study of the compound in older children with type 2 and 3 SMA.

“Spinraza, gene therapy and the Roche compound all induce [trigger the production of] SMN. We need all three of these therapies approved,” Burghes said. “Why? Because it allows competition in the marketplace. If these therapies have to compete against each other, the price will be immediately reduced. So one of the first things we need to do is push forward these clinical studies.”

He explained that “we’ve developed treatments that work very well when given early. They work less well when given in symptomatic cases. That means they don’t have as dramatic an effect, and we would all like the most dramatic effect. So which therapies can you put together to get a more dramatic effect, and how should those go together?”

Newborn Screening for SMA Crucial

Burghes also would like to know “what else should we put with SMN that could further improve treatments of both early and late symptomatic patients, what would those look like, should we put things that enhance muscle function together with an SMN inducer, and how do therapies get better from what they are?”

Last year, the U.S. patient advocacy group Cure SMA started a grassroots campaign to convince all 50 states to pass legislation requiring newborn screening for SMA.

“If you have newborn screening in place, and you treat everybody, you will probably have fewer issues,” Burghes said. “That’s why getting newborn screening onto the books and in place is extremely important.”

So far, only Missouri and Minnesota have passed legislation requiring the testing. Other states, including Massachusetts, New York and Utah, are planing to implement it, and a bill is pending in the Ohio Legislature to do likewise, he said.

“But in Europe, it’s more complicated. It seems to depend on which country you’re talking about,” Burghes said. “I have not seen anything come up in a legislative manner for SMA newborn screening, but I do feel the U.K. is beginning to move in this direction. So is France.”

He added that “in Denmark, the authorities have decided that the benefit from Spinraza across all SMA types is not sufficient to justify the cost. But the effects are so dramatic in a newborn that this, in my view, should overturn that decision.”