Case Report Alerts Physicians About Link Between SMA and Ketoacidosis

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patients can be more prone to a life-threatening metabolic imbalance called ketoacidosis, which causes the blood to become acidic, a case report highlights.

In patients with neuromuscular diseases like SMA, physicians should be particularly suspicious of this complication so that it is recognized and managed early.

The case report “Severe ketoacidosis in a patient with spinal muscular atrophy” was published in the journal CEN Case Reports.

The report describes the case of a young 36-year-old man diagnosed with SMA type 3 who was admitted to the emergency room at American University of Beirut, Lebanon, due to episodes of vomiting and stomach pain.

The wheelcahir-bound patient was not taking any medication, but had started a diet to lose weight a week before symptoms appeared.

Interested in SMA research? Check out our forums and join the conversation!

Apart from the SMA symptoms of muscle weakness and atrophy (muscle wasting) his physical examinations revealed no further problems.

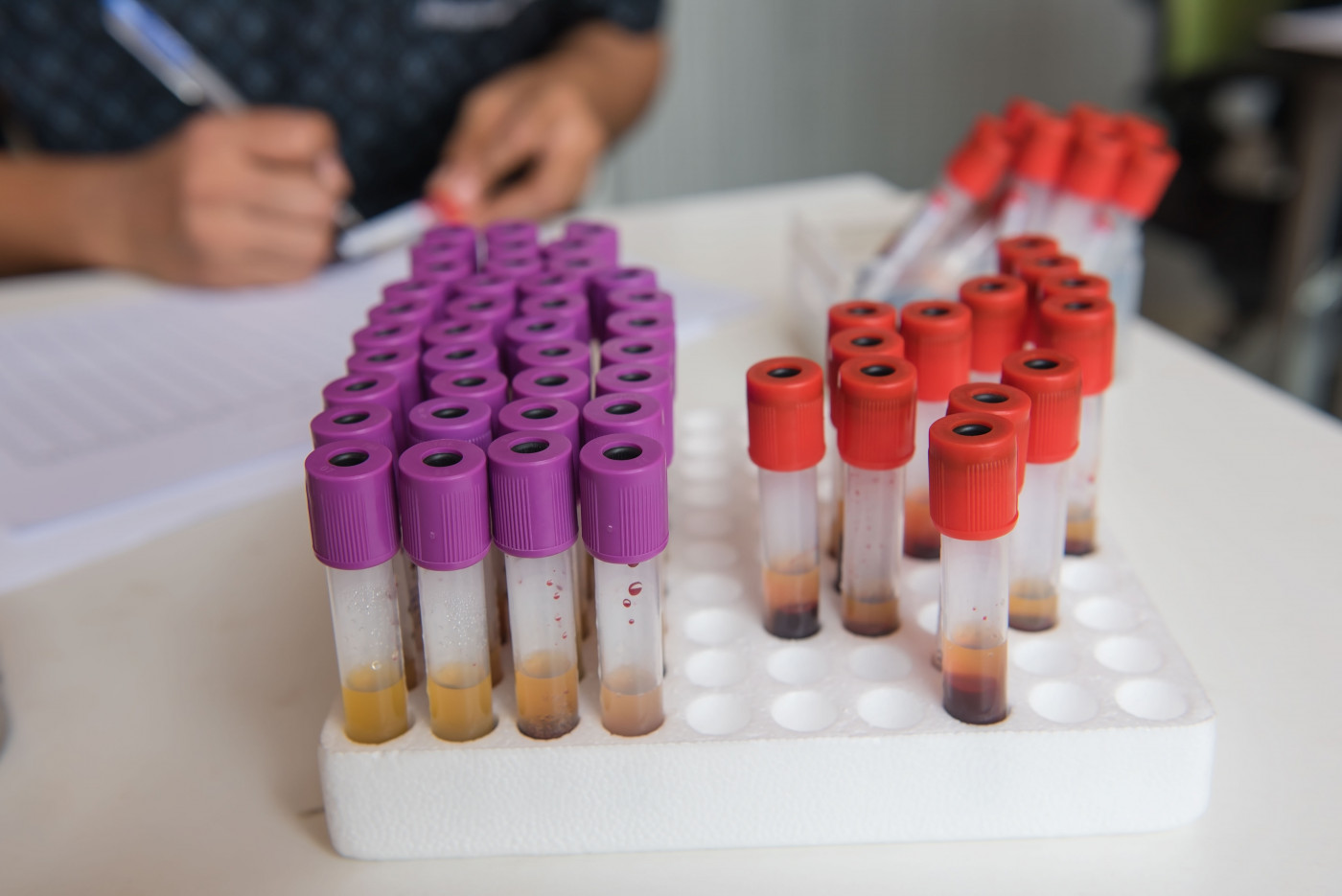

However, blood tests indicated the presence of metabolic acidosis and high levels of blood acids called ketones. (Metabolic refers to metabolism, the chemical processes cells undertake to live.)

The analysis was consistent with a condition termed ketoacidosis, a serious complication that occurs when the body starts breaking down fat too rapidly to produce energy. As a consequence, the liver processes the fat into a “fuel” called ketones, which are acidic molecules that cause the blood to become acidic.

Ketones normally are produced during periods of sugar shortage (fasting, starvation, intense exercise) as the body starts to break down fat for energy. If ketones are produced and accumulate too quickly in the blood and urine, they become toxic and eventually lethal.

People with diabetes, for instance, who have problems using sugar as an energy source, are especially at risk of developing this complication.

The patient in this case report was treated successfully for ketoacidosis, using intravenous hydration with saline and treatment with dextrose and sodium bicarbonate. Three days after admission, all his laboratory parameters were back to normal and the patient was discharged. He was advised to avoid fasting and to eat a balanced diet.

Although SMA is a neuromuscular disease, several metabolic dysfunctions have been described in people with the disease.

As the severity of the patient’s ketoacidosis was inconsistent with starvation alone, researchers proposed that other reasons associated with SMA may have contributed to this complication.

Possible factors included low muscle mass, disturbed fatty acid metabolism, hormonal imbalances and defective glucose metabolism.

When ketones are produced, they are consumed mostly by muscle fibers. In people with reduced muscle mass, such as in SMA, ketone consumption is lower, promoting ketoacidosis.

In addition, muscle atrophy reduces the supply of amino acids (building blocks of proteins) as a source of energy and the body shifts toward the breakdown of fats and producing ketones.

“Ketoacidosis is an under-recognized entity in patients with neuromuscular diseases and requires a high index of suspicion for prompt diagnosis and management,” the researchers concluded.