Spinraza improves some aspects of sleep for children with SMA type 1

After 6 months of treatment, patients were falling asleep sooner, spending more time asleep

Written by |

Treatment with Spinraza (nusinersen) improved certain aspects of sleep for children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 1, according to a recent study.

Patients were falling asleep sooner and spending more time asleep at night after six months of treatment. There was also evidence of alterations in electrical activity suggesting the children could be woken up more easily, but the findings were not statistically significant.

While the findings indicate an “overall better sleep pattern” with Spinraza, they’ll need to be confirmed in larger and longer studies, according to the researchers in “Sleep architecture and Nusinersen therapy in children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy type 1,” which was published in Sleep Medicine.

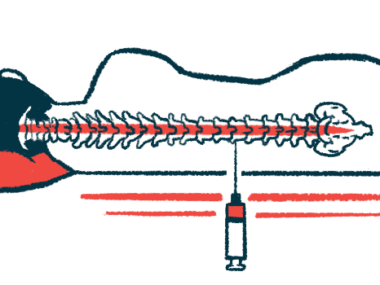

Biogen‘s Spinraza has been widely used to treat SMA since its U.S. and European approvals in 2016 and 2017, respectively. It boosts production of the SMN protein that’s lacking in SMA.

Clinical trial and real-world evidence demonstrate a range of benefits from it, including significant motor improvements and prolonged survival, but ongoing studies are still assessing its effects on other SMA symptoms, such as sleep difficulties.

Progressive weakness in the respiratory muscles can lead to apnea, when breathing starts and stops during sleep, and patients may have trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting enough deep/restful sleep. People with SMA types 1 and 2 also have altered patterns of electrical activity in their brain during certain sleep phases, research indicates.

Does Spinraza change sleep patterns?

In this study, scientists examined 16 patients with SMA type 1 at a clinic in Italy to see if Spinraza could modify these examples of sleep architecture and microstructure. Four boys and 12 girls received Spinraza at a median age of 44 months (a little over 3.5 years) under an expanded access program before its approval in Europe.

Polysomnography, a technique to record brain waves during sleep, was used to evaluate the patients’ sleep architecture before starting Spinraza and again about six months later after they’d received five infusions of the therapy.

All but two children were receiving long-term invasive or noninvasive ventilation support at the time of the study. Breathing parameters during sleep showed evidence of improvements with Spinraza, but the findings weren’t statistically significant. Still, after six months, the children were falling asleep significantly faster than they had been before treatment and spent a greater percentage of time in bed asleep.

Measures of sleep microstructure didn’t significantly change after six months, but certain alterations suggested that patients could be more easily roused from sleep with treatment.

In their previous study, the scientists found sleep alterations indicating SMA patients might be harder to rouse from sleep than healthy people. Impaired control of being brought out of sleep in SMA could result from the loss of SMN in brain regions important for sleep-wake cycles, the researchers said.

Although not statistically significant, the new findings offer “cautious optimism” that the benefits of Spinraza on sleep would be more evident in larger and longer studies. The scientists said that some of their findings may have failed to reach significance due to the small number of patients studied and the relatively short follow-up time. The delay in starting Spinraza — the patients were diagnosed at a median of about 6 months old, but didn’t start treatment until after age 3 — may also explain the “limited effects on sleep parameters,” they said.