COVID-19 made life with SMA more difficult, parents and doctors say

In surveys, they note changes in therapies and stresses particular to Sweden

Written by |

Limited social interaction and difficulties in accessing needed medications and physical therapy were consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, parents and grandparents of children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Sweden reported.

In online surveys and chats, family members spoke of having to take charge of their child’s physiotherapy and care, with some needing to stop working as at-home care assistance became more difficult to get.

Healthcare professionals also reported finding their work more stressful, particularly with the annual assessments required of patients under a disease-modifying SMA therapy like Spinraza (nusinersen) — the only one approved in Europe in 2019 — as continued support for such repeat-use treatments in Sweden is determined by yearly reports of disease stability.

“The stress connected with [Spinraza] assessments became even more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic because families had most of the responsibility for training and habilitation,” the researchers wrote. “The healthcare professionals sometimes felt as if they were assessing parental efforts.”

Adaptations in SMA caregiving routines demanded by a pandemic

The study, “Experiences of families of children with spinal muscular atrophy and the healthcare professionals supporting them during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide study,” was published in the Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine.

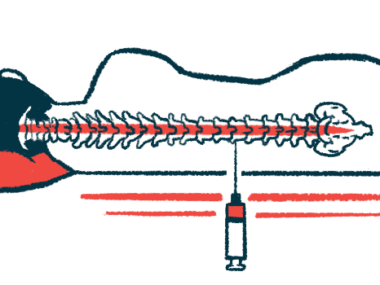

SMA results in the progressive dysfunction and loss of motor neurons — the nerve cells that control voluntary movements — leading to disease symptoms like muscle weakness and wasting. Weakness in respiratory muscles can make breathing more difficult and patients more vulnerable to respiratory infections.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant social restrictions, which particularly affected people living with serious conditions and in need of regular contact with an array of healthcare professionals. However, “little is known about how families of children with SMA and the healthcare professionals supporting them experienced the COVID-19 pandemic,” the researchers wrote.

Researchers across Sweden surveyed 39 parents (24 mothers and 15 fathers) and three grandmothers of 28 children with SMA at two times: September-October 2021 or March-April 2022. Most of the children were girls (57%), and most had SMA type 3 (39%), followed by SMA type 2 (32%), and SMA type 1 (25%).

Survey questions ranged from whether children and family members contracted COVID-19 to how the pandemic affected SMA treatment, overall care, and access to Spinraza, given as a maintenance therapy by intrathecal (spinal canal) injection once every four months.

While 12 children and nine parents tested positive for COVID-19, none of the children became seriously ill.

Parents in written responses noted the social isolation required and the difficulties brought by things like limited school attendance, and the changes in work and social life they demanded. “We are completely exhausted,” one wrote in the 2021 survey. “Our child is very social and is desperate to start socializing again.”

Some, however, felt that the restrictions increased friends’ and family members’ understanding of the limitations in contact they had demanded before the pandemic, like during a flu season.

“We feel people have more respect and understand our situation more now than before. Before, they didn’t understand our fear of infections, or why we were so careful and didn’t want to socialize if someone had a cough or a cold. Now they do,” a parent said in a follow-up phone interview.

Seven parents were selected for phone interviews and 18 took part in follow-up focus group sessions with healthcare teams that included physicians, nurses, an occupational and physical therapists.

Added demands and other changes seen as ‘doable, but harder’

Parents and grandmothers noted limited access to physical therapy, particularly hydrotherapy, and changes in Spinraza treatment, in terms of where they could access the therapy or in its delivery. Parents also spoke of having to take charge of their child’s physical therapy needs, like stretching exercises, possibly given with guidance via telehealth.

“Now there is even more responsibility on us parents to make sure that all the physiotherapy are performed. Another change is that only one parent is allowed to come along when our child receives nusinersen [Spinraza] treatment. It’s doable, but it’s harder,” one parent said in a telephone interview.

Families with at-home care assistance noted how access to such personal care diminished and affected their quality of life, with some needing to leave their jobs as a result.

“Personal care attendants cancelled if they had even the slightest symptom, or if they [the personal care attendants] had met anyone with symptoms, they were often on sick leave,” a parent wrote in the 2021 survey.

Changes in routines also were reported by healthcare professionals, with particular mention of stresses due to annual treatment assessments or face masks that limited communication with children. These assessments also are required in Sweden for continued use of the oral daily treatment Evrysdi (risdiplam), approved for the European Union in March 2021.

“I want the families to feel that we are on the same side, not against each other. We find the situation very difficult,” one medical professional said in a focus session.

Canceled care visits, often with little advance notice, also led to feelings of time and resources being wasted.

“Parents reported a heavy burden, as much of the responsibility of the child’s needs fell on them” while healthcare professionals continued their work much as usual, but also “reported a change in their role to becoming more of an assessor; they faced the ethical dilemma of having to score children’s performance and carry out the right assessment in terms of the child’s medication treatment,” the researchers concluded.

“It may be of value to find ways for healthcare professionals to get together, support one another, and discuss their role as assessors. It might also be useful to find out how each family coped with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and offer further support if needed,” they added.