Inflammatory signaling molecules may predict response to Spinraza

Levels of certain molecules shift toward inhibiting inflammation in patients

Written by |

In people with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) treated with Spinraza (nusinersen), levels of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules tend to decrease while levels of anti-inflammatory signaling molecules tend to increase in the months after starting treatment, a study has found.

Findings also suggested that changes in certain inflammation-regulating molecules may help predict how patients respond to Spinraza treatment.

That’s according to the study “Cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid as a prognostic predictor after treatment of nusinersen in SMA patients,” which was published in Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery.

SMA is caused by mutations that lead to a deficit of the SMN protein. As a result, motor neurons, which are the nerve cells that control movement, sicken and die. Some data suggest neuroinflammation (inflammation in the nervous system) may play a role in the disease’s progression.

Inflammation coordinated by signaling molecules called cytokines

Inflammation is coordinated by signaling molecules called cytokines. Some cytokines are pro-inflammatory, prompting immune cells to go on the attack, while others are anti-inflammatory, acting to “put the brakes” on immune activity to prevent unneeded inflammation.

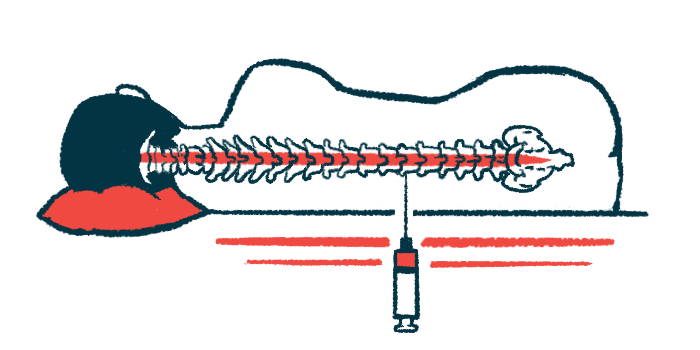

Spinraza was the first SMA treatment to be widely approved. It works to boost levels of the SMN protein, thereby slowing or stopping the progression of SMA. In this study, scientists in China examined how treatment with Spinraza affects levels of certain cytokines in the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

The analysis focused on three cytokines: a pro-inflammatory cytokine called tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and two anti-inflammatory cytokines called interleukin-10 (IL-10) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1).

The study included 15 people with SMA, nine with type 2 disease and six with type 3. Cytokine levels were measured before starting Spinraza, then again after about two and six months on the treatment, which is given by injection into the spinal canal. Most of the patients experienced clinically meaningful improvements in measures of motor function during the six months of Spinraza treatment, the researchers noted.

Results showed average levels of the pro-inflammatory TNF-alpha declined significantly over six months on Spinraza, while levels of the anti-inflammatory MCP1 significantly increased. IL-10 levels also tended to increase, though the difference wasn’t statistically significant (meaning it’s mathematically plausible the change could be random chance).

‘Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines decreased’

“The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines decreased, while those of protective factors that inhibit inflammation increased during [Spinraza] treatment,” the researchers concluded.

In further analyses, the researchers found a statistically significant link between decreased levels of IL-10 during Spinraza treatment and greater improvements in scores on the Revised Upper Limb Module, which is a standardized test of arm and hand function.

Collectively, the data suggest these cytokines “may serve as potential biomarkers for future investigations to monitor disease progression and treatment efficacy” in SMA, the researchers concluded. The team stressed, however, that this study was limited to a small number of patients followed for only a few months, so larger studies will be needed to validate the results.

Spinraza is sold by Biogen, which was not involved in this study.