Previously unknown breathing abnormality seen in SMA type 2

Pseudo-obstructive sleep-disordered breathing is caused by muscle imbalance

Written by |

A previously unknown breathing problem — called pseudo-obstructive sleep-disordered breathing — has been discovered among people with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 2, a study reveals.

This unusual breathing pattern during sleep is caused by an imbalance between the SMA-related weakness in the chest muscles and the relatively unaffected diaphragm muscles, both of which contribute to breathing. While the events’ severity increased with the progression of the disease, they were successfully treated with noninvasive breathing support.

“If confirmed, these events could represent SMA-specific outcome measures,” the researchers wrote in “Pseudo-obstructive sleep disordered breathing – definition and progression in Spinal Muscular Atrophy,” which was published in Sleep Medicine.

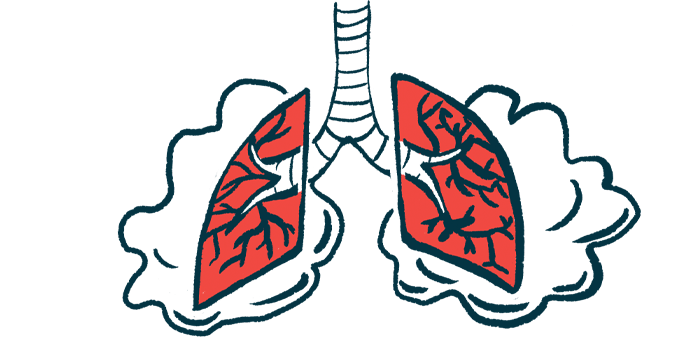

SMA is marked by progressive muscle weakness and poor muscle tone, including the muscles in the chest for breathing. During inhalation, these intercostal muscles expand, allowing the lungs to fill with air. At the same time, the diaphragm, a thin muscle that extends across the bottom of the chest, or thoracic, cavity, contracts, also expanding the lungs. Because of the the intercostal muscles’ progressive weakness, SMA patients may have breathing complications such as reduced lung function and difficulties clearing lung secretions. These problems get worse during sleep.

One such problem, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) occurs when breathing stops and starts during sleep due to tissue in the upper airways collapsing. OSA in SMA may also feature paradoxical breathing, when the chest wall moves in when breathing in and out when breathing out, the reverse of normal movements. OSA is detected by polysomnography (PSG), also known as a sleep study, wherein breathing rate, heart rate, blood oxygen levels, and brain activity are monitored during sleep.

Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing is another complication of SMA and happens when an upper airway obstruction is present during sleep. The severity of the obstruction can’t be detected with PSG.

‘Pseudo-obstructive’ breathing events

Researchers at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London suggest some of these obstructive events may be “pseudo-obstructive” instead of truly obstructive. They said an imbalance between the SMA-related weakness in the intercostal muscles and the relatively preserved diaphragm muscle may cause these pseudo-obstructive events.

To find out, researchers reviewed the results of 18 sleep studies from six patients, ages 3-13, with SMA type 2 who’d yet to receive disease-modifying therapies. The follow-up after the first study ranged from three to six years.

At the time of it, four patients were breathing room air without assistance, while two were receiving noninvasive ventilation (NIV) support. All had been using a cough assist device to help expel lung secretions.

Besides the standard sleep apnea events, all the patients on all PSGs showed features consistent with pseudo-obstructive events — the presence of paradoxical breathing, the absence of increased breathing rate during the event, and a lack of compensating breath after the event.

Also, researchers noted a “chest wall paradox” during pseudo-obstructive events, primarily in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the stage of sleep when most dreams occur. This breathing pattern is marked by the diaphragm contributing more to breathing than the intercostal muscles. During non-REM sleep, patients showed features of the “abdominal paradox,” which features a relative reduction in the movements of the abdominal versus the chest muscles.

Among the three patients who could still breathe without assistance, the number of pseudo-obstructive events increased from the first sleep study to the latest. The two patients on NIV remained stable over a five-year follow-up due to compensating increases in NIV air pressure.

“This response to treatment further strengthen the unique physiopathology of the pseudo-obstructive events linked to respiratory muscle weakness and the need to discriminate them from other events to establish a tailored ventilatory approach,” the researchers said.

Lastly, periods of pseudo-obstructive apneas, or breathing stoppage, were shorter than hypopneas (shallow breathing) at the first sleep study (median, 9.5 vs. 13.6 seconds) but not the latest. Paradoxical breathing also evolved over time during both REM and non-REM sleep.

Pseudo-obstructive sleep-disordered breathing “is prevalent in these patients as the expression of the known imbalance between intercostal and diaphragmatic weakness,” the researchers concluded. “The number of pseudo-obstructive events tended to increase with age and disease progression and was reduced by NIV initiation.”

More research on larger groups of SMA patients is planned to “further define their clinical implications,” the researchers said.