2 type 1 SMA babies show signs of restored motor neuron connections

Improvements may be due to Spinraza and Zolgensma treatment: Case reports

Written by |

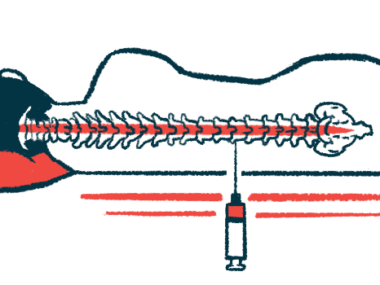

Treatment with Spinraza (nusinersen) and Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec) led to increases in the electrical activity of motor neurons — the specialized nerve cells that control voluntary movement — for two young children with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), according to a new report.

Findings from tests of electrical activity in the patients’ muscles suggested that the treatment may have helped to restore some connections between motor neurons and muscle cells that had been lost due to disease progression, researchers said.

“Although clinical improvement in patients with SMA after these treatments has been reported, changes in electrophysiological findings have rarely been reported. … In this paper, we report [such] changes … over time in two cases with SMA type 1 after treatment with [Spinraza] and [Zolgensma],” the scientists wrote.

One of the children who received the two therapies is now able to sit unsupported, a milestone not usually achieved without treatment.

The study, “Changes in electrophysiological findings of spinal muscular atrophy type 1 after the administration of nusinersen and onasemnogene abeparvovec: two case reports,” was published in BMC Neurology.

Babies with SMA type 1 first treated with Spinraza, then Zolgensma

SMA is characterized by the death and dysfunction of motor neurons due to mutations in the gene SMN1, which produces the SMN protein. Zolgensma, which has been widely approved to treat SMA, is a one-time gene therapy designed to deliver a healthy copy of this gene to motor neurons.

Spinraza, the first disease-modifying therapy approved to treat SMA, works by increasing the levels of functional SMN by acting upon the SMN2 backup gene.

Now, scientists in Japan reported on the cases of two children who were diagnosed with type 1 SMA — the most common and among the most severe forms of the genetic disease — in the first months of life. Both patients were treated with Spinraza for a few months immediately following the diagnosis, then were administered Zolgensma.

At the latest follow-up, one of the babies — now age 2.5 — is able to sit unsupported and stand with a leg brace. Without treatment, children with SMA type 1 rarely achieve any typical motor milestones.

The other child was a few months older and had more advanced disease when she started on treatment. At the time she was given Zolgensma, this patient had a feeding tube to get nutrients. She was able to feed orally, however, by about a year after gene therapy. She is now age 2 and although she does not have head control, she is able to roll to her side.

Before starting on SMA treatment, and then again at ages 1 and 2, both of the children underwent tests to measure the activity of their motor neurons and muscles.

Specifically, researchers measured compound muscle action potentials, known as CMAPs, for large nerves in the arms and legs. CMAP basically is a measure of the electrical activity that occurs when a motor neuron fires and a muscle contracts in response.

Prior to starting on treatment, both children had very low CMAP values. However, these values increased substantially at follow-up assessments done after Zolgensma administration.

“In our patients, the CMAP amplitudes of the median and tibial motor nerves were significantly lower than those of healthy children of the same age before the treatment. However, they increased over time after the treatment,” the researchers wrote.

More studies needed on treatments’ effects on motor neurons

In the first child, the CMAP measuring in the tibial nerve of the leg was actually within normal ranges by age 2, even though the child had not achieved typical leg-based motor milestones like standing unsupported. At the same time, CMAP in the median nerve of the child’s arm was below normal — even though the child had no notable issues with arm movement.

“In patient 1, the CMAP amplitude of the tibial [leg] nerve had better recovery compared to the median [arm] nerve. However, clinical improvement was greater in the upper limbs, so the difference in the degree of improvement in CMAP between upper and lower limbs may not necessarily reflect the degree of clinical improvement,” the researchers wrote.

Prior to treatment, measures of muscle activity in both patients revealed fibrillation potentials, which are tiny spontaneous activations of muscle cells that occur when a muscle becomes decoupled from its motor neuron, as happens in SMA when the motor neurons die off.

After treatment, there was still some evidence of lost connections between motor neurons and muscle cells. However, the researchers also noted a type of electrical muscle activity called high-amplitude motor unit potentials that were not seen before treatment.

According to the researchers, high-amplitude motor unit potentials are known to occur when a muscle loses its connection with a motor neuron, but then the connection is restored — a process called reinnervation. As such, this result “suggested that peripheral nerve reinnervation occurs after these treatments,” they said.

The researchers stressed, however, that this finding alone “does not necessarily prove recovery of motor neurons,” emphasizing a need for more detailed studies and further evaluations of how treatments affect motor neuron and muscle activity in SMA patients.