SMA Newborn Screening Expands as More States Enact Mandatory Testing

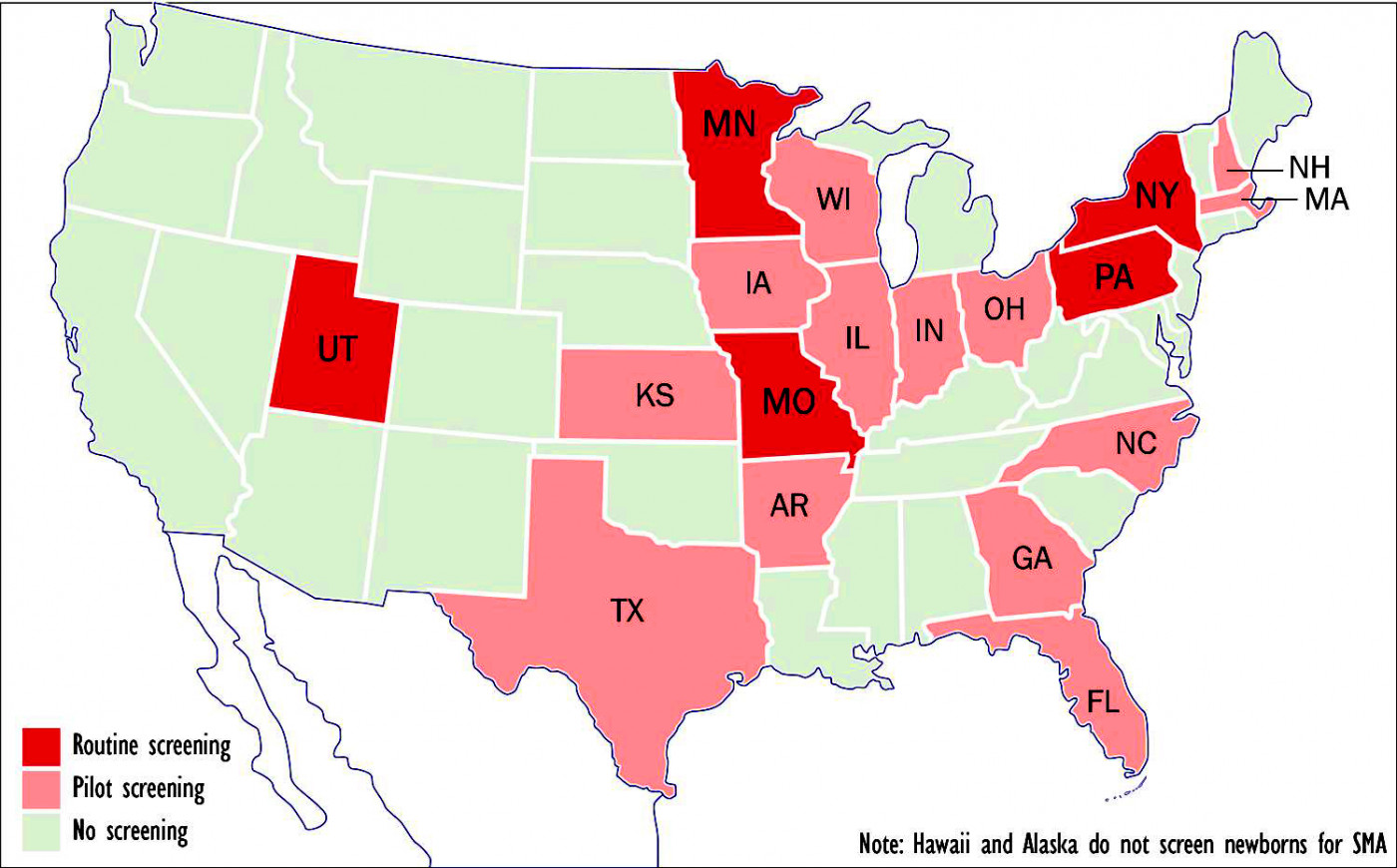

Five states now routinely screen newborns for spinal muscular atrophy; another 13 are in the process. (Graphic by Armando H. Portela)

Five states — Missouri, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania and Utah — now routinely screen newborn babies for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), while another 13 have passed laws either requiring such screening or are in the process of doing so.

Pennyslvania began testing infants for the neuromuscular disease on March 1, according to the nonprofit group CureSMA, which has urged a nationwide screening program for years.

Currently, the average infant with SMA type 1 isn’t diagnosed until five months of age, said the Chicago-based organization — meaning that babies don’t receive treatment during the critical early weeks and months of life when, research suggests, it could be most effective.

According to a March 2018 report submitted to the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children — a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — newborn screening of the roughly four million babies born in the U.S. each year could avert death or the need for mechanical ventilation in 48 infants by their first birthday.

“Most newborn screening programs surveyed stated that it would take between one and three years to implement screening for SMA,” according to the 105-page report. “Screening for SMA requires few additional resources when multiplexed with SCID [severe combined immunodeficiency], which is included on most state newborn screening panels.”

Are you on Spinraza? Join our forums and share your experience with other patients and caregivers.

It added: “SMA screening methods have high (100%) positive predictive value, and no false positives have been reported to date when screening for deletions of exon 7 on both alleles.”

Jaimie Vickery, vice-president of policy and advocacy at Cure SMA, said more than a dozen states have asked that SMA be added to their newborn screening panels.

Missouri leads the way

In July 2017, Missouri became the first state to institute screening for SMA. The legislation, signed into law by then-Gov. Eric Greitens, was sponsored by Rep. Becky Ruth. Minnesota and Utah soon followed.

“Newborn screening, combined with early treatment, is the best chance we have to change the course of SMA for the next generation,” Cure SMA President Kenneth Hobby said at the time. “We envision Missouri becoming the model that other states can follow as we work to move SMA newborn screening forward.”

States that have begun pilot screening or are considering doing so include Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin. Screening is based on detection of a deletion in exon 7 in the Survival Motor Neuron 1, or SMN1, gene.

In January, Arkansas lawmakers approved a bill adding SMA to the state’s newborn screening panel. And on Feb. 15, the Florida Genetics and Newborn Screening Advisory Council voted unanimously to add SMA to its newborn screening panel. Florida — now the nation’s third most populous state — has 18 months to implement SMA newborn screening.

“The law requires us to do the screening, but haven’t started screening yet,” said Ann Purvis, the Arkansas Health Department’s deputy director for administration. “We’ll be working with other states that have an approved process in place to replicate the process. It’s going to take several months before we’re able to do this.”

Purvis, speaking by phone from Little Rock, told SMA News Today that such things are normally done through a regulatory process instead of bypassing a state law.

“However, it was an effort by legislators who became aware of the issue through personal stories, and they didn’t want us to go through a regulatory process. So I worked with them to pass that law,” she said.

The promise of gene therapy

Purvis said Arkansas hospitals have been testing newborns for various diseases since the 1960s. Based on the records, she expects to see maybe five or six babies born with SMA annually in her state. According to Cure SMA, about 115 Arkansans have the disease, while more than 55,000 of the state’s three million inhabitants carry it.

Treatment is already covered by private insurance plans and the state’s Medicaid program. The new bill requires insurers to cover testing for SMA without adding to patients’ out-of-pocket charges. Purvis said testing would increase what the department charges hospitals by $9.10. Currently, testing costs $121 per sample. Hospitals pass charges along to patients or their insurance plans.

Neurologist Jerry Mendell of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has done groundbreaking work in both SMA and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

He said that with Biogen’s breakthrough drug Spinraza (nusinersen), now on the market for more than two years, and the new AveXis gene therapy Zolgensma (previously known as AVXS-101) awaiting imminent approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, more and more states, including Ohio, see the logic in testing for a disease that was considered incurable not long ago.

“There has to be an incentive for the states to approve it. This an outgrowth of the clinical trial we initiated in 2014, because the treatment was so promising and it’s saving so many lives,” said Mendell, a principal investigator at Nationwide’s Center for Gene Therapy.

“There wasn’t any treatment for SMA before Spinraza and gene therapy came along,” he added. “Kids would die by 10 months of age, but in our trial, all the patients have survived for up to three years. So obviously, there’s great hope now.”

Mendell, who played a key role in the development of Zolgensma, said his clinical trial (NCT02122952) was “pioneering” because it used an extremely high dose of AAV9 virus — 2.0×1014 vector genome per kilogram of body weight — on 12 of the 15 patients in the study; the other three received a low dose. All subjects had two copies of the SMN2 backup gene.

“There had never been any clinical trials that used this much virus,” he said. “It had generally been frowned upon, and the gene therapy community considered that much virus a potential risk, although we had cleared it with the FDA based on our preclinical results.”

What next for RUSP?

SMA was first nominated for inclusion in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) in November 2008. But the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children didn’t request a formal review of evidence for SMA newborn screening until May 2017. Finally, in July 2018, Alex Azar, secretary for U.S. Health and Human Services, officially approved adding SMA screening to the RUSP.

The committee’s next meeting is April 23-24 at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Rockville, Maryland. To register for that meeting, which also will be webcast, click here.

“Although this is a significant and important step, it is only the beginning,” according to Cure SMA. “Each state decides what conditions it will include in its screening panel. We must continue to work to make sure that every state screens for SMA.”

Arndt Rolfs, CEO of Centogene — a German diagnostics company that specializes in genetic testing for rare diseases — said the best national screening programs are in the U.S, Canada, France and Britain.

“We all agree that there’s nothing better than testing at the very beginning, before an individual might develop the risk for specific symptoms,” said Rolfs, interviewed earlier this month at the 2nd International Congress on Advanced Treatments in Rare Diseases in Vienna. “But screening is still a problem. It’s so difficult — even in a wealthy country — to establish a standardized definition of newborn screening.”

Rolfs, whose company calls itself “the world’s largest diagnostic portfolio for 3,500 diseases,” suggested that the cost of testing is not what’s preventing more states from including SMA in their mandatory newborn screening programs.

Rather, he said, “they’re all afraid that if they identify the patients, they’ll have to start lifelong treatment” for the disease. At $750,000 for the first year of Spinraza and $375,000 for every year after, those lifelong treatments can deplete government budgets very quickly.

Asked why all 50 states aren’t already screening for SMA now that the disease appears on the RUSP, Mendell said it’s a subject fraught with complexities.

“I think the responsibility has been divided, in a sense,” he told SMA News Today. “It’s a states’ rights issue and I’m certainly not going to play politics here, but the way it’s set up, when the advisory committee recommends something, it achieves overwhelming support in most states. There are very few that would refuse once it’s approved at a national level. Maybe some states don’t feel qualified to be knowledgeable about every single disease.”