Living on Borrowed Time

Written by |

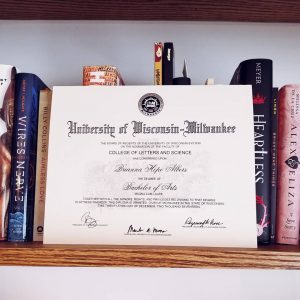

I officially graduated with my bachelor’s degree in December, but I only just received my diploma in the mail. I’ve been expecting it for weeks now, but it was still kind of surreal, opening the manila envelope and seeing my name in fancy script, “magna cum laude” underneath.

There was never any doubt that I would graduate. But there was never a guarantee that I would make it to college in the first place. Following my diagnosis with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the doctors gave me nine years to live. I somehow managed to prove them wrong, but the death sentence is something I’ve carried with me, something I’ll carry for the rest of my days.

My parents didn’t tell me right away, so for most of my childhood, I had no idea how sick I was. I knew I was different. I knew I needed to be careful. I learned at a young age to pay attention to coughs and sniffles. If someone around me was sick, I was expected to move. It didn’t matter if I was in class, if moving meant interrupting a classmate’s speech, if moving meant drawing attention to myself. It was life or death. It was survival. A cold could land me in the hospital; a cold could kill me. But I was a kid. I wanted to wear short sleeves in 40-degree weather, just like everyone else, and the concept of death was too vague at the time to really mean anything.

There were a few times that death coalesced into something concrete, something meaningful. The first being my spinal fusion, as I was curled on my dad’s lap in the waiting room, trying to shut out the terrified screams of the other kids. Lying on the operating table, blinking up into achingly bright lights, I tried to remember what it felt like to have my mother’s hand in my hair — knowing the anesthesia might never wear off, knowing I might just sleep forever. And the second: fainting during a respiratory treatment, waking up to my aunt, terror in her eyes, and my older cousin dialing 911.

I found out right about the time I graduated high school. I don’t really remember how, or why — just that I did, that suddenly life seemed far more fragile than it used to. Things that had always been a given, an implicit, no longer were: grad parties; the paraprofessional I had all throughout high school, eyes red from crying; my sophomore English teacher, who brought his wife, the faceless woman my classmates and I had only heard about; my pediatrician and pulmonologist, who had known me since I was a baby. Things that could’ve been taken away in an instant.

As a child, I spent a birthday in the ICU. I’d been there for a while, so the nurses knew me, my parents, and family members who came to visit. They bought me a necklace from the gift shop as a birthday present, a gold heart inlaid with glittery stones in the shape of my first initial. I wore the thing a couple of times when I was younger, but could never really get past the memories associated with it: wilted balloons, the sharp press of a needle, watered-down light streaming through the blinds.

The day of my grad party, I wore it for the last time. It was a symbolic gesture. I still have the necklace and couldn’t bring myself to get rid of it. But it meant something to me, a kind of reclamation.

I’ll never be free of the death sentence. All those nights in the NICU and ICU, the ER, my father flicking mindlessly through cable channels. I’ll never not see the necklace and think: I should be dead. Just like I’ll never not look at my diploma and think: I was never supposed to graduate high school. In a way, though, it’s important to have those reminders. I spent my youth oblivious to what should’ve been. I wasn’t ungrateful, I just wasn’t grateful enough. And now, as a college graduate and master’s degree candidate, I have the chance to make things right. To live the way I should’ve all those years ago, which is to say on borrowed time — time that was never mine to begin with.

***

Note: SMA News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of SMA News Today or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to spinal muscular atrophy.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.