Challenging the Assumptions for Effective SMA Drug Administration

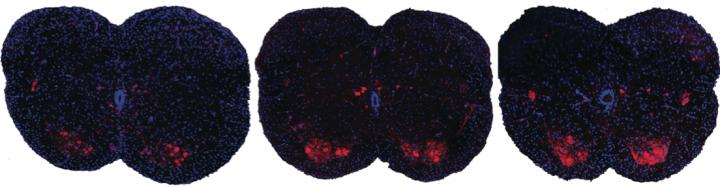

Spinal muscular atrophy is the leading genetic causes of death for infants, but there is currently no approved treatment. A team of scientists from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has a potential drug to treat the disease that is injected into the cerebrospinal fluid of patients. But the researchers have discovered that in mouse models the drug is effective even when injected subcutaneously, and it is not necessary in the central nervous system. Shown here are spinal sections from three different mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Systemic drug treatment (middle panel) increases the presence of motor neurons (red spots) over the untreated mice (left panel). Surprisingly, the results are very similar when treatment is excluded from the central nervous system (right panel), suggesting a possible new path for spinal muscular atrophy drug treatment. CREDIT A. Krainer/ Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

A study published by a team of researchers at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) suggests that a drug to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in a mouse model is effective when administered subcutaneously in peripheral tissue and not just in the central nervous system (CNS). This important discovery is challenging the currently held assumptions of what successful drug treatment options for patients should look like. The study was published in the current issue of The Journal of Genes and Development.

A study published by a team of researchers at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) suggests that a drug to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in a mouse model is effective when administered subcutaneously in peripheral tissue and not just in the central nervous system (CNS). This important discovery is challenging the currently held assumptions of what successful drug treatment options for patients should look like. The study was published in the current issue of The Journal of Genes and Development.

SMA is an inherited disease (genetically determined) that affects 1 in 10,000 infants born annually in the U.S. The prognosis is poor for babies with SMA Type I (there are three distinct types of SMA) in which most patients who are diagnosed die within the first two years. SMA is caused by an abnormal or missing gene known as the Survival Motor Neuron gene (SMN1 gene), which is responsible for the production of a protein essential to motor neurons that allow for muscle contraction. Without this protein, lower motor neurons in the spinal cord degenerate and die.

Currently there is no cure for SMA and the standard of care protocol consists of managing symptoms and preventing complications. That standard of care protocol could look remarkably different in coming years if CSHL researchers and their collaborators at Isis Pharmaceuticals meet their goals.

[adrotate group=”3″]

Professor Adrian Krainer, PhD., the head of the CSHL lab in which the discovery was made stated , “It is largely believed in our field that SMN is essential in the CNS – not in peripheral tissues like the limbs or liver – so most efforts have been focused on increasing full-length SMN levels in the CNS. But over the last few years, evidence has been building that challenges our assumptions about the pathology of the disease. The question is: do we need to increase SMN levels in the CNS, in peripheral tissues, or both?”

In challenging these assumptions, Dr. Krainer and the rest of his team, including those with whom he collaborated at Isis Pharmaceuticals, developed a method to restore SMN production only in peripheral tissues, therefore allowing researchers to understand the physiological mechanisms of the drug administration for both the interior and exterior of the CNS. After administering the drug subcutaneously in mice, SMN levels increased in both CNS and peripheral tissues. These results indicate in newborn mice, but not in older mice, some of the drug injected in the periphery can reach the CNS. This treatment showed an almost complete cure rate in the mice afflicted with SMAand successfully demonstrated within a mice model, peripheral tissue plays a critical role in compensation for CNS deficiency and preserves the important functions of motor neurons.

The results from this paper are very optimistic in regards to future drug therapy targets and utilization for patients diagnosed with SMA. Currently, Isis Pharmaceuticals is conducting clinical trials with the drug and preliminary results show promise in human patients.