Zolgensma Linked in 3 Cases to Serious But Treatable Blood Disorder

Written by |

Some children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) may develop thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) — a rare condition characterized by blood abnormalities — following treatment with Zolgensma, a study reports.

A serious complication, TMA was resolved with supportive or specific treatment in all three cases identified (0.6%) among the 500 children treated with Zolgensma, a gene therapy, through July 1, 2020.

Clinicians should be aware of this potential complication despite its rarity, and closely monitor patients’ platelet levels, as recommended in Zolgensma’s label. A low platelet count is a main indication of TMA, the researchers noted.

The study, “Thrombotic Microangiopathy Following Onasemnogene Abeparvovec for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Case Series,” was published in The Journal of Pediatrics.

Novartis’ Zolgensma was approved in the U.S. in May 2019 to treat all SMA types in children up to age 2. This year, it also became available in Japan for the same patient group, and in Europe for almost all SMA types in children weighing up to 21 kilograms (about 46 pounds).

The therapy uses a modified and harmless virus to deliver a working copy of SMN1, the mutated gene in SMA, to cells. Due to the body’s natural immune reaction against the carrier virus, it can only be given once.

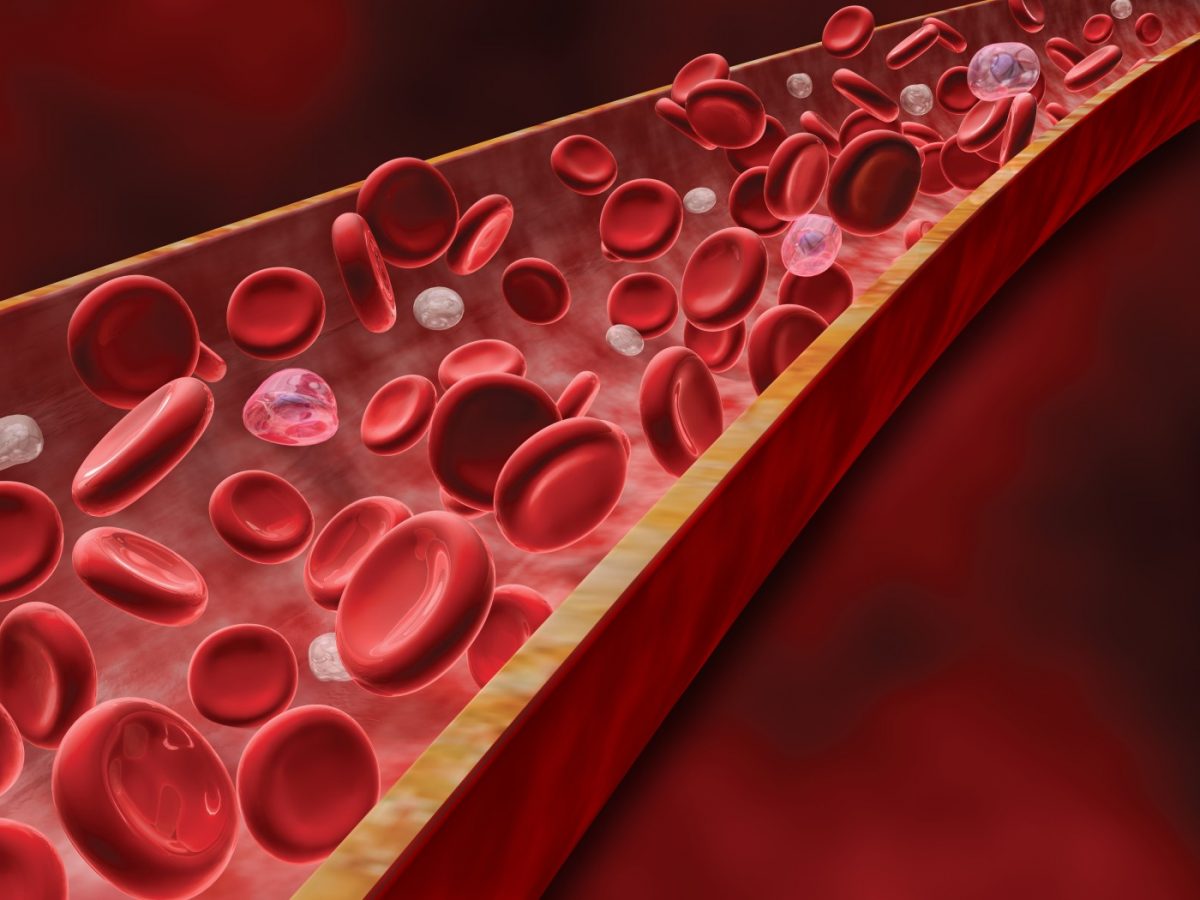

Still, children can develop immune reactions after the single dose, which may increase the levels of liver enzymes — an indicator of liver damage — and drop those of platelets, tiny blood cells responsible for normal blood clotting.

For that reason, children start immunosuppression with prednisolone or its equivalent on the day before they are given Zolgensma, and are advised to continue such treatment for a total of 30 days. Their liver health and platelet counts are also monitored before treatment, and at regular periods afterward.

TMA is a rare condition characterized by hemolytic anemia (the destruction of red blood cells), low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia), and the formation of blood clots in small blood vessels that can injure the kidneys.

While it can have a genetic cause, TMA is also associated with the use of some medications, including vaccines, immunosuppressive treatments, and antibiotics, as well as with herbal supplements. Treatment-induced TMA is thought to result from immune-mediated reactions, or a dose- or duration-dependent direct toxic effect.

Researchers at Novartis, in collaboration with colleagues at U.S. and Australian institutes, reported three cases of TMA associated with Zolgensma’s use. All have been completely addressed and successfully treated.

These cases were identified through a specific search of the Novartis Global Safety Database, which includes Zolgensma’s safety data from clinical trials, open-access programs — through which patients can access a therapy before its approval — and its post-approval clinical use. The search identified, in total, roughly 500 children given the therapy through July 1.

Two of the three affected children (a 5-month-old girl and a 14-month-old girl) were part of a long-term registry study called RESTORE (NCT04174157), while the third (a 1-year-old girl) was treated through an open-access program in Australia. Launched by AveXis (a Novartis subsidiary, now known as Novartis Gene Therapies), RESTORE’s main goal is to follow SMA patients given the gene therapy as part or outside of a clinical trial.

The children’s doctors were contacted for additional information from medical records. Regarding TMA symptoms, all three showed low platelet counts and hemolytic anemia, and two girls had signs of kidney injury.

These cases shared several similarities, the researchers concluded after analyzing the children’s data. All three girls developed TMA about a week after Zolgensma dosing, and vomiting was a possible early symptom for two of them.

Vomiting “potentially resulted in inadequate prednisolone absorption,” the researchers wrote.

Two had also been previously treated with Biogen’s Spinraza, two had received recent vaccines, and two had infections with particularly harmful bacteria either prior to or shortly after Zolgensma’s use.

Researchers noted that such bacterial infections and recent exposure to vaccines may have contributed to TMA. Whether Spinraza’s use increased the risk of Zolgensma-associated TMA is not yet known, the study noted.

Increased activation of the complement system, a part of the immune system known to be associated with TMA, was evident in two children. The 14-month-old also had a family history of chronic kidney disease of unknown cause, and genetic testing revealed mutations of unknown significance in two genes; mutations in one of them are linked to a specific type of kidney disease.

All three girls recovered from TMA after two to 12 weeks (about three months): one with supportive care only, and the others with additional treatments, such as increased corticosteroids (immunosuppressive medications) and those promoting the replacement or supply of blood or blood components (plasmapheresis and blood transfusions).

Researchers noted that the time between Zolgensma dosing and TMA development suggested an immune-mediated reaction, and that TMA has been reported in studies of other viral-based gene therapies.

Clinicians should follow recommendations for monitoring platelet counts, since a low platelet count is “a key feature of TMA,” the scientists wrote. If this laboratory finding is present, additional TMA-related testing should be performed.

“Early recognition of TMA is imperative, as TMA may require therapeutic intervention … to lessen associated morbidity and mortality,” the researchers wrote.