Spinraza Delays Found Not to Directly Affect Children in Italy

Written by |

Delayed Spinraza (nusinersen) treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic did not directly result in a worsening of symptoms in children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a small study suggests.

Any worse motor function that occurred during this period was attributed to a lack of response to the therapy or difficulties in family situations, the researchers wrote.

The study, “Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children With SMA Receiving Nusinersen: What Is Missed and What Is Gained?,” was published in the journal Frontiers in Neurology.

Spinraza is a disease-modifying therapy for all types of SMA, and has been shown to slow the progression of muscle weakness and atrophy (shrinkage) that are characteristic symptoms of the disease.

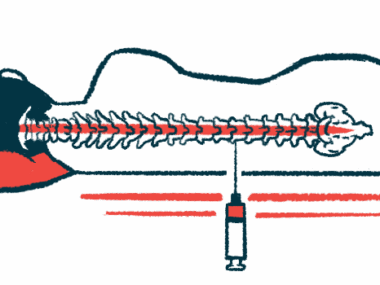

Spinraza requires an intrathecal administration — injection directly into the fluid surrounding the spinal cord. These infusions are typically carried out in a clinical setting by specially trained medical staff.

Early in 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, and medical centers that provide Spinraza had to postpone planned infusions for some children.

This study focused on the Veneto region of Italy, where a pediatric palliative care (PPC) program treats children with SMA. In its PPC Centre of Padua, some medical activities were changed or suspended during the first lockdown. During this time, Spinraza therapy was considered a health emergency, and maintenance doses were rescheduled to comply with pandemic restrictions but did not exceed intervals of six months.

Because of the benefits of Spinraza infusions and other supporting medical programs, such as nursing and physiotherapy, interruptions due to the pandemic could have affected SMA patients’ health, quality of life, and families.

To understand the extent of the pandemic’s impact on children undergoing Spinraza treatment, researchers based at the Padua University Hospital examined medical records of SMA patients whose Spinraza treatment was discontinued due to restrictions.

In addition, a questionnaire was given to parents and children (6 and older) at the therapy’s first administration after the suspension. The survey contained questions about perceived muscle strength, swallowing, and breathing, as well as questions about personal feelings and fears during the lockdown.

“The present work aims to assess the clinical and social issues that arise for PPC children and their families from a delay in [Spinraza] infusions, resulting from the contingent COVID-19 restrictions,” the team wrote.

The study included 25 children (13 females), ranging in age from 2 to 15. Of these, 11 (44%) responded to Spinraza at the last infusion before lockdown, with eight of the 11 (73%) receiving early treatment within one week of a genetic diagnosis.

Motor function was assessed with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP), the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination, and the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale–Expanded (HFMSE).

At the first clinical visit after the lockdown period, nine patients (36%) showed a reduction in functional scores compared with five (20%) who showed improvement. Of those nine patients who had worse disease, none had initially responded to Spinraza.

Eight children (32%) experienced a delay in infusions, ranging from 26 to 91 days (three months). Among these, marginal changes in the functional scores were noted, except for one patient with a 59-day delay in Spinraza treatment who did not initially respond.

Each family received two phone calls per month from nurses during the lockdown, and the physiotherapist made 64 video calls and six home visits. No child needed emergency room care or was hospitalized.

Long-term assessments were also investigated at the second infusion after lockdown. Here, Spinraza was administered four months after a previous infusion without delay and compared with the last clinic visit before the lockdown.

Functional scores were lower (worse function) in 10 patients (40%) and higher in eight participants (32%). In three cases, there were larger decreases in functional scores. These included one patient whose treatment was delayed by 59 days (-7 points on the HFMSE scale), another patient with a single support parent (-4 points on the CHOP scale), and one with parents who experienced depression due to job loss (-4 points on the CHOP scale).

In one case, functional scores greatly improved, with a 7-point increase compared with before lockdown. This patient had two caregivers during the lockdown. Another patient who experienced worse scores at the first post-lockdown visit improved at the second evaluation “due to better compliance with supportive therapies (cough machine),” the researchers wrote.

All parents — mostly mothers (92%) — completed the questionnaires. Among these, five (20%) did not see a change in their child’s muscle strength, 12 (48%) saw a worsening, and eight (32%) saw improvements. No change in swallowing was reported by 20 parents (88%), two (8%) felt swallowing worsened, and one (4%) saw improvements.

No changes in breathing function were reported by 20 parents (80%), two (8%) saw improvements, and three (12%) felt it was worse and had to increase respiratory support. The worse function was mainly thought to be due to the suspension of outpatient physiotherapy (40%) or the delay in Spinraza treatment (24%).

Regarding the interruption in therapy, three parents (12%) were not worried while the remaining parents were slightly worried (20%), quite worried (12%), very worried (32%), or extremely worried (24%). Twelve parents did not ask for additional help during the lockdown, and 13 reported the benefits of extra PPC support.

Of the children 6 years and older, 13 responded to the questionnaire, with ages ranging from 7 to 15. Here, 10 (77%) reported no change in muscle strength, two said it was worse, and one felt a great improvement. One saw improvement with swallowing, and 12 (92%) reported no difference.

Nine patients (69%) reported no changes in breathing, three (23%) said it improved, and one (8%) reported worsened breathing, resulting in additional assisted ventilation. Seven (53%) said they were not worried about treatment interruption, one was slightly worried, three were quite worried, one was very worried, and another was extremely worried.

During the lockdown, children mostly missed school and seeing their friends (61%) or taking lessons (23%). Two children (16%) missed going to physiotherapy sessions or hydrotherapy.

“Although a detailed statistical analysis was not possible due to the small sample size, no correlation between a delayed treatment and changes of functional scores emerged over the short-period evaluations … and the immediately following months,” the researchers wrote. The worsening that was observed in both the short- and long-term evaluations “cannot be attributed to the delay in infusions but to a difficult family situation of the patients.”

“This evaluation has been carried out both in the short and long term after the first lockdown period and can be considered as a ‘proxy’ of a situation of a possible delay in administration or management of infusions, due to other different causes,” the researchers wrote.