Endothelial Cell Defect Causes Microvasculopathy in SMA Mice

Preclinical research focuses on restoring survival motor neuron protein

Written by |

Microvasculopathy — damage to small blood vessels — occurs in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and it can be made better by systemic SMN-restoring treatment, a new study reports.

Survival motor neuron protein (SMN) is the protein that is defective in SMA. The available SMA treatments increase the levels of SMN protein exclusively in the central nervous system (CNS, the brain and spinal cord) or both in the CNS and peripheral organs.

The new study highlights the importance of treatments that act on the periphery, namely in the vascular system.

“Our findings provide mechanistic insights into … SMA microvascular complications, and highlight the functional role of SMN in the periphery, including the vascular system, where deficiency of SMN can be addressed by systemic SMN-restoring treatment,” the team wrote.

The study “Microvasculopathy in SMA is driven by a reversible autonomous endothelial cell defect,” was published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

SMA is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene that reduce the levels of survival motor neuron, a protein critical for the function and survival of motor neurons, which are the nerve cells that control movements.

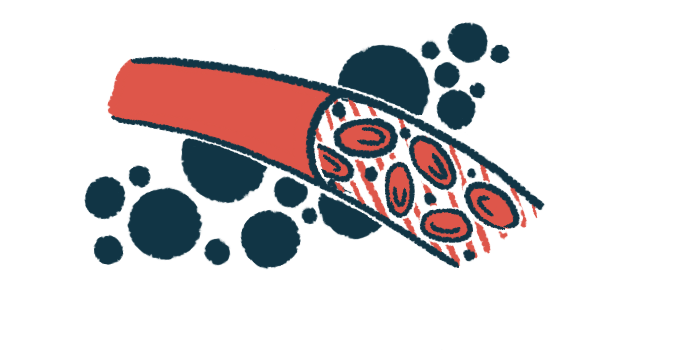

Vascular problems were described in severe cases of infantile SMA, and were replicated in a mouse model of the disease. They include finger and skin necrosis (the death of cells and tissues), vascular thrombosis, and fewer capillaries (small blood vessels) in skeletal muscle. Patients also might present cardiovascular problems, such as congenital heart disease and heart failure.

Now, researchers in the U.K. identified a decrease in the complexity of retinal blood vessels — a parameter used to assess the health of blood vessels in the CNS — in 11 children with SMA (median age 11 years), when compared to 23 healthy children (median age 9).

The effects were replicated in a mouse model of severe SMA — called transgenic SMA Taiwanese mice — that present similar vascular effects in the retina.

“Taken together, these data reveal an important microvascular pathology of the retina in the SMA mice, likely related to SMN protein deficiency,” the researchers wrote. “This phenotype [disease features], present in both SMA patients and mouse models, points toward fundamental defects in angiogenesis [the formation of new blood vessels] and microvascular development in the vessels supplying the CNS in SMA.”

In mice, vascular damage preceded the loss of neurons in the retina, emerging as an indicator of later neuronal damage in SMA.

Using antisense therapy

Importantly, the researchers reversed the disease effects in mice retinal blood vessels by restoring SMN protein levels. They did so by using an antisense oligonucleotide (AON, molecules that modulate gene/protein expression) to increase SMN levels.

“We show that antisense therapy, delivered systemically at birth to increase SMN protein expression, can normalise the microvascular defect in these mice,” the researchers wrote.

Vascular health depends on endothelial damage and repair. When endothelial cells — located in the inner surface of blood vessels — are damaged, they detach from the vessels’ walls and enter blood circulation (circulating endothelial cells, or CEC). In SMA patients, the team found that the number of these circulating cells is increased, with higher levels observed in severe forms of the disease (with disease severity being determined by the number of SMN2 copies).

Moreover, the vascular repair mechanism was found to be decreased in SMA patients, meaning lower levels of endothelial progenitor cells — cells important for vascular repair — in blood circulation.

Overall, “SMA patients show defective microvascular networks, increased vascular injury and a reduced capacity for vascular repair, consistent with a generalized microvasculopathy,” the team wrote, further suggesting that the number of circulating endothelial cells might be “a novel cellular biomarker for SMA-associated vasculopathy.”

When researchers treated endothelial progenitor cells obtained from SMA patients (in vitro experiments, with cells maintained in dishes) with the same antisense oligonucleotide used for the retina studies in mice, the number of endothelial progenitor cells increased, which could potentially ameliorate vascular repair defects.

Finally, researchers discovered that vascular pathology in SMA is related to a defect in the ability of endothelial cells without SMN to form blood vessels. This effect was observed in endothelial cells obtained from patients and mice.

“Our data identify microvasculopathy as a fundamental feature of SMA, which is driven by reversible … endothelial cell defect,” the team concluded. “In light of all these findings, our study suggests that therapeutic strategies for SMA should also include the correction of the SMN deficiency in the periphery, including the vascular system.”