Determined Life of Service Keeps Man With SMA Type 2 Going at 66

Stephen Mikita, diagnosed in 1957, retired from government for full-time advocacy

Written by |

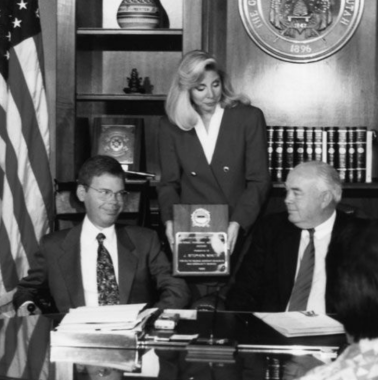

Stephen Mikita, who retired as assistant attorney general for Utah in 2021, advocates for the disabled. (Photo courtesy of Stephen Mikita)

Doctors expected Stephen Mikita to live for six months after his diagnosis, in the late 1950s, with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 2.

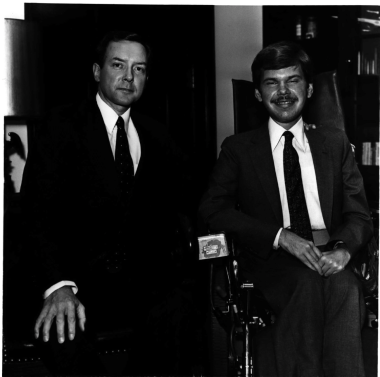

Now 66, Mikita can look back on a successful career in law, first as a law clerk to the late U.S. Sen. Orrin Hatch, a Republican representing Utah, and then a 39-year stint as an assistant attorney general for that state.

Mikita said support from his family and friends throughout life with SMA and his continued efforts to improve healthcare for all minority populations have contributed to his longevity with the disease.

Stephen Mikita, right, was a law clerk for U.S. Sen. Orrin Hatch in the early 1980s. (Photos courtesy of Stephen Mikita)

“There was just that sense that my life has meaning by engaging with others and assisting them in navigating some of the burdens and some of the structural and attitudinal barriers that seemingly preclude them from enjoying life,” Mikita said in a video interview with SMA News Today.

He’s used his passion for helping others in the disabled community, both in his role as assistant attorney general and now as a patient advocate for diversity in clinical trials and medical device development. He retired from public service in 2021.

Since 2020, Mikita has been an adviser to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) All of Us Research Program, which aims to create a health database of 1 million Americans. He chairs the Participant Advisory Board for Vibrent Health, which built the participant portal and application for the project.

The NIH initiative can help researchers learn more about risk factors for diseases, what treatments work best for people of different races, and how to lead healthier lives.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime longitudinal study that tries to gather information and data from populations that reflect our nation’s population and continues to ask questions,” Mikita said. “Researchers can take deeper dives in that data and launch their own ancillary studies to take a deeper dive into understanding why is it that I’ve lived so long with my disease and others haven’t, and that question can be replicated through every single disease in our world.”

Mikita also hopes the diverse group of study participants will lead to better medicine for people of color, who, he said, have been victimized in the past by the healthcare system and have had poor social determinants of health, which include conditions like living environment, transportation, food, and cost of care.

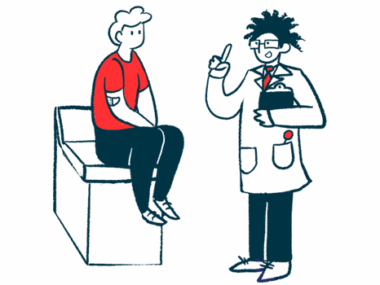

Medical advances improving quality of life

Mikita uses his thumb to navigate his power wheelchair and speaks and participates in virtual calls. He requires 24-hour care and needs to be repositioned by his assistant every 10 minutes.

But since starting the oral therapy Evrysdi in December 2021, he says he’s regained some 20 years in various aspects of his functionality. He mentioned having a better lung capacity, more stamina throughout the day, no pain in his shoulders or neck, a greater ability to swallow, increased neck mobility, and greater strength in his thumbs.

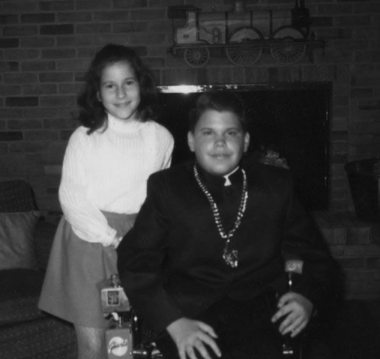

Stephen Mikita, then 12, is shown with his younger sister Judith in 1968.

“There is longevity for more of us than I could have ever imagined. It is breathtaking to me that I have lived long enough to see these breakthroughs and these therapies and these procedural drugs being developed and dispersed,” Mikita said.

Mikita has experienced a number of changes that improve an SMA patient’s lifespan, including more specific clinical care guidelines for SMA, the 1995 discovery of the survival motor neuron 1 gene that causes SMA, and the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved therapy for SMA in 2016.

While there is a general lack of mortality studies that go back to Mikita’s birth, a 2007 study showed SMA type 1 patients born between 1995 and 2007 had a 70% lower risk of death compared with patients born between 1980–94. Survival probabilities for SMA type 2a patients with no need for mechanical ventilation and the like were 74.2% and 61.5% at ages 40 and 60 years, according to a 2020 Neurology article.

SMA diagnosis

Being diagnosed in 1957, at 18 months old, with SMA was a very different experience for Mikita’s family than for the family of a child diagnosed today. No disease-modifying therapies were available; no social media support groups for people affected by SMA. It was an emotional roller coaster — his family went from one reassuring appraisal that Mikita would learn to walk to another, three months later, where doctors said he had only months to live.

By age 4, Mikita’s condition was stable. He couldn’t walk, yet at the same time, he wasn’t losing function either. It started to seem like a future with SMA was possible, especially after he learned of a former president who used a wheelchair.

The January 1960 edition of Look magazine featured the former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In 1960, Mikita’s father showed him the January edition of Look magazine, which featured a 23-page picture biography of the late President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The president was diagnosed with polio in 1921, and he used a wheelchair during his 1932 presidential campaign and while in office, though he kept it mostly hidden from the public eye.

“That filled my life with a sense of purpose and a mission and a roadmap of what I could accomplish in real life in a wheelchair with a severe disability,” Mikita said.

Roosevelt’s life was also part of the reason he studied politics in addition to religion at Duke University, where he graduated in 1978.

While at school he converted to his mother’s religion, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In his 2011 book, “I Sit All Amazed,” Mikita writes that his mother often prayed by his side during his hospitalizations, including a harrowing recovery from spinal fusion surgery, and he was frequently surrounded by Mormon missionaries. Writing a paper about the Mormon Church for a religion class at Duke further cemented his conversion and led him to Brigham Young University law school.

Americans with Disabilities Act

While earning his law degree, Mikita clerked for Sen. Hatch, who was a co-author of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) about a decade later. Mikita said being a clerk for Hatch had an impact on Hatch’s support for the ADA, which prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities.

Mikita is honored by then Utah Gov. Norman Bangerter in 1993.

“I believe that Sen. Hatch often credited me with helping to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act, and that was kind of a way of saying that he remembered me,” Mikita said, adding that Hatch valued his out-of-the-box thinking. “That opened his eyes to the fact that individuals with disabilities have the skills, abilities, and education to become employed with reasonable accommodations and that we should be given a chance to work.”

Mikita further proved his point in becoming an assistant attorney general for Utah after law school. While noting it was by no means easy to get through law school and find employment with a disability, he always considered it a matter of when rather than how, and he never doubted his abilities.

He learned from his mother, he said, that all it takes is the buy-in from one person to help turn a vision into reality. Hundreds could say your dream is impractical or impossible, but the one person willing to listen and understand makes all the difference.

Continued purpose in serving

While his mother stayed by his side throughout some of the most challenging times with SMA, his siblings always made sure to include him in childhood games. Mikita batted a Wiffle ball and his sister Judith would run the bases for him. He also played football, using his motorized wheelchair to rush the quarterback and wait in the end zone for an accurate pass from his older brother Bill.

The support from his family and others engaged in concerted efforts to make the world more accessible to him also helped lead to his position as assistant attorney general. In that role, he represented state agencies in charge of protections and services for people with disabilities and for incapacitated adults who can’t self-advocate or self-protect.

Based on his life experience, hundreds of appearances before the Utah Supreme Court, and representing others with disabilities, Mikita has now taken on a full-time advocacy role that gives him a continued sense of purpose.

Even with the ADA, Mikita said a lot remains to be done to help integrate people with disabilities into society. He hopes to raise public awareness around the roughly one-third of Americans dealing with some kind of chronic or severe disease. People with disabilities are the largest minority population in the U.S., Mikita said, and there is a need to ensure they aren’t left out, early on, of conversations that shape policy.

Mikita also works to improve healthcare for other minority communities, particularly people of color. In addition to his other roles, he serves as chair of the Disease State Awareness subcommittee and is a member of the steering committee for MedTech Color, a leadership group founded by people of color in the medical device industry.

Mikita also advises other organizations involved with disability and minority inclusion. All he has done since his 2021 retirement is part of the purpose that has made him successful with a condition that was expected to take his life 64 years ago.

“To live with a chronic disease, you’ve got to be a very resilient individual who is willing to adapt to change and to hold fast to a belief that notwithstanding certain, frequent circumstances, you have the ability to navigate through those challenges and still arrive at a state of happiness and purpose,” Mikita said.