Nerve signals can help track Spinraza response in SMA kids: Study

CMAP, measure of nerve health, showed gains after 18 months of treatment

Written by |

The strength of nerve signals to muscles may serve as a marker of disease severity, and as a means to track responses to Spinraza (nusinersen) treatment, in children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the findings of a new study suggest.

The research showed that children with SMA type 3, a milder disease type, had higher compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes in hand, arm, and leg nerves than youngsters with more severe types. CMAP, a measure of the number and health of functioning nerve projections, increased after about 1.5 years of treatment with the approved disease-modifying therapy, the data also showed.

CMAP amplitude also was associated with motor function, “indicating that it may be a possible biomarker for evaluating motor ability in SMA,” the team wrote.

The study, “Electrophysiological Changes in Pediatric Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Results From an Observational Study,” was published in the journal Muscle & Nerve by researchers in China.

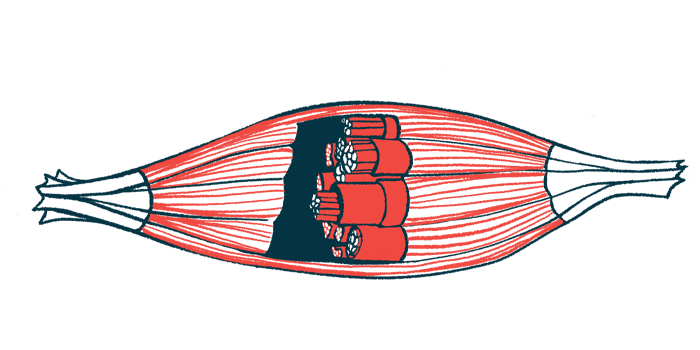

SMA typically is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene that lead to low levels of the SMN protein, as well as the progressive loss of motor neurons, which are the nerve cells that control movement. This results in symptoms such as muscle weakness and wasting.

Investigating CMAP amplitude in SMA kids vs. healthy children

Earlier studies have suggested that CMAP may be a biomarker of disease progression and patients’ response to treatment. However, according to the researchers, that work was focused mainly on nerves in the arms and hands.

“The motor nerves of the lower limbs … in children with SMA have not been sufficiently investigated,” the team wrote.

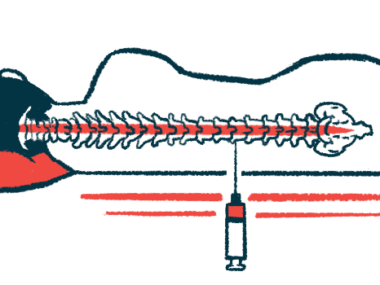

To learn more, the researchers now looked at CMAP amplitude in the hand, arm, and leg nerves of children with SMA compared with healthy youngsters. The team also evaluated the effects of Spinraza, which has been approved for about a decade as an SMA treatment.

Their study enrolled 47 children with SMA, with a median age of 23 months, or just younger than 2 years. Most were diagnosed with SMA type 2 (68%), followed by type 3 (23%) and type 1 (9%). About 60% were boys, and 70% were able to sit. Four (9%) could walk.

At diagnosis, children with SMA had significantly lower CMAP amplitudes than their peers in the same age range without neuromuscular disease. This was the case for the motor nerves of the hand and arm (ulnar and medial), thigh (femoral), and lower leg (peroneal and tibial nerves),

In addition, children with SMA type 3 had significantly higher CMAP amplitudes in arm nerves and in the tibial and right peroneal nerves of the leg than those with type 2 or type 1 disease. There were no differences in the femoral and left peroneal nerves between SMA types.

Further, CMAP amplitudes in the nerves of the lower leg were higher in children able to walk than in those who could not.

Nearly 90% of SMA children in study were given Spinraza

Overall, 42 children (89%) were treated with Spinraza alone or in combination with Evrysdi (risdiplam), another approved SMA treatment. At their most recent measurement before starting Spinraza, children with type 2 and 3 SMA showed the highest CMAP in the median nerve (4.06 and 9.75 mV), while the lowest was registered in the femoral nerve (0 and 0.4 mV).

According to the researchers, “the marked reduction in the CMAP of the femoral nerve may be explained by the involvement of proximal muscles [closer to the trunk] in SMA.”

Nine children, seven with type 2 and two with type 3 SMA, underwent CMAP assessments before and six and 18 months (1.5 years) after starting standalone or combination Spinraza therapy. After six months, children with type 2 SMA experienced a significant increase in CMAP in the median and peroneal nerves, with no other significant differences.

We found that CMAP amplitudes remained stable throughout the natural history of symptomatic SMA but showed a potential increase after 18 months of [Spinraza] treatment.

After 18 months, CMAP amplitudes in hand, arm and leg nerves significantly increased from the start of treatment in all children evaluated. There were no differences comparing children treated with Spinraza alone with those receiving it with Evrysdi.

“We found that CMAP amplitudes remained stable throughout the natural history of symptomatic SMA but showed a potential increase after 18 months of [Spinraza] treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Further analysis demonstrated that CMAP amplitudes at the study’s start were associated with the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale-Expanded (HFMSE) scores in all nerves evaluated. HFMSE is an assessment of overall motor function.

According to the researchers, “further studies are required to determine whether the observed gradual amplitude increase in patients with SMA is treatment-related,” and whether CMAP amplitude may be used as a biomarker for treatment response.