No Unwanted Immune Responses Found for SMA Children on Spinraza

Treatment does not lead to changes in inflammatory markers: study

Written by |

Spinraza (nusinersen) treatment is safe in children with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and does not cause unwanted immune responses, a study confirmed.

The study, involving case reports on three children with SMA who developed elevated levels of white blood cells after Spinraza treatment, also found no changes in levels of inflammatory markers.

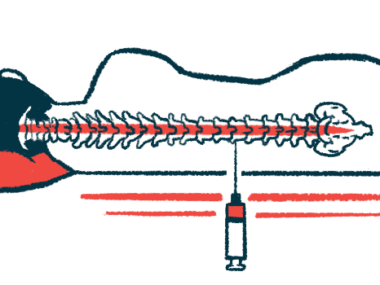

“Our results further confirm that repeated intrathecal delivery [injections into the spinal canal] of gene-targeting therapies is safe, also when focusing on markers of inflammation,” the researchers wrote, noting that these findings add to the “still limited” data on the long-term effects of such treatments for neurodegenerative disorders like SMA.

Higher levels of the anti-inflammatory protein interleukin-10 (IL-10) coincided with elevated white blood cells in these patients, suggesting IL-10 may be a marker to assess potential treatment-related immune responses.

Titled “Inflammatory markers in cerebrospinal fluid of paediatric spinal muscular atrophy patients receiving nusinersen treatment,” the study was published in the European Journal of Pediatric Neurology.

Checking for immune responses, inflammation

Spinraza is a disease-modifying therapy approved for all types of SMA. It is delivered via repeat intrathecal (into the spinal canal) injections, and helps slow or halt the progression of muscle wasting and weakness that marks SMA.

Clinical trials supporting Spinraza’s approval demonstrated few side effects other than those associated with the injections themselves. Since then, however, other adverse events have been reported, specifically related to an inflammatory response. Yet, a thorough investigation of inflammatory markers over the course of Spinraza therapy has yet to be conducted.

Now, a team of researchers at the UMC Utrecht Brain Center, in the Netherlands, set out to systematically investigate a range of inflammatory markers in patients with SMA types 1, 2, and 3 undergoing Spinraza treatment.

They found three SMA children who developed elevated levels of white blood cells, called leukocytes, after receiving Spinraza, but lacked clinical signs of inflammation or immune responses. Typically, leukocytes are a sign of an inflammatory response.

Because it was unclear which proteins could be accurately measured in patients’ cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) — the liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord — researchers first analyzed CSF samples from the three children with the elevated leukocyte counts. These patients were matched to a control group without increased leukocyte counts for sex, age, SMA type, disease duration, and motor function.

Results showed that the anti-inflammatory protein IL-10 was consistently elevated in each sample with increased leukocyte levels, but could not be detected in any of the other samples.

Also, the neuroprotective protein MCP1 slowly but consistently increased with treatment over time, especially in patients with type 3, and may therefore be a biomarker to monitor Spinraza’s effectiveness, the team noted.

Based on these initial experiments, the team selected seven protein markers reliably detected in CSF to measure the impact of Spinzara treatment. The screen included IL-10, IL-1B, IL-6, and TNF alpha — all related to inflammation — alongside markers associated with SMA, motor nerve cell function, or the neuromuscular system, including C5a, ANG1, and MCP1 (also called CCL2).

Researchers then assessed a group of 38 patients with available CSF samples collected before treatment (baseline), then two weeks after starting Spinzara, and again 10 months later. Among them, four were diagnosed with SMA type 1, 22 with type 2, and 12 had type 3.

Across this larger group of patients, the team found no link between any of the inflammatory markers and Spinzara therapy. MCP1 levels, however, showed an increasing trend over time with treatment.

For those with type 3 disease, this increase was statistically significant at 10 months compared to baseline levels, “indicating a possible neuroprotective mechanism associated with [Spinzara] therapy,” the researchers wrote.

Our results further confirm that repeated intrathecal delivery [injections into the spinal canal] of gene-targeting therapies is safe.

Further analysis found no relationship between MCP1 levels and age at disease onset, delay of therapy start, measures of motor function, or number of SMN2 gene copies.

These results confirmed that the use of intrathecal injections of Spinraza to treat children with SMA is well-tolerated and safe, the researchers said.

“In rare patients with elevated leukocyte numbers, we were able to measure IL10, suggesting that IL10 may be a promising candidate to monitor immune response to intrathecal injections in patients for which this is relevant,” the team concluded.

“MCP1 (CCL2) showed a modest but consistent increase with treatment over time, especially in type 3 children, and may therefore be an interesting biomarker candidate for future research,” they added.