Proper nutrition can be lacking in children on Spinraza, study finds

Feeding difficulties among likely reasons diets richer in fats and sugars

Written by |

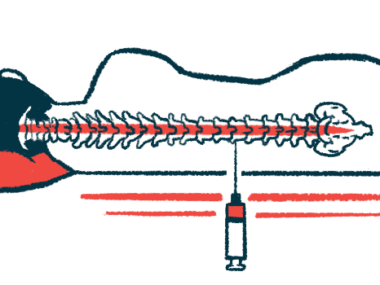

Difficulties with adequate nutrition and feeding persist among children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) types 2 and 3 being treated with Spinraza (nusinersen), a Norwegian study reports.

Important nutrients, such as protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals, often were consumed in lower-than-recommended amounts by these patients, while sugars and saturated fats were in higher amounts. And problems with feeding continued for many patients, especially those with type 2 disease, due to weakened muscles needed for chewing, swallowing, and moving food about.

“Systematic monitoring of nutritional status continues to be important in pediatric patients with SMA II and SMA III on disease-modifying treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Nutritional status and dietary intake in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy types II and III on treatment with nusinersen,” was published in Clinical Nutrition Open Science.

Interview and questionnaire study into nutrition for 40 children with SMA

Nutritional problems are common in SMA, arising from factors such as muscle weakness, gastrointestinal disorders, and metabolic changes. But their prevalence can vary by SMA type, with patients with types 1 and 2, for example, often finding swallowing or chewing more difficult than those with SMA type 3.

However, few studies have evaluated SMA nutritional needs in recent years, and particularly since the arrival of three disease-modifying therapies: Spinraza, Evrysdi (risdiplam), and Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi). These treatments aim, in different ways, to target the underlying cause of SMA by boosting production of the SMN protein that patients lack.

Researchers in Norway looked at the nutritional status of 40 children and adolescents with SMA type 2 and type 3 who had started treatment with Spinraza at a median age of 7.2. Most of these young patients were on regular diets, although one type 2 child was reliant on a feeding tube, and four (three with type 2 and one with type 3) were using supplemental nutritional drinks. (Spinraza was added to the country’s public health plan for children with SMA in 2018, allowing reimbursement.)

“Bulbar impairment and feeding difficulties are well-known comorbidities of SMA and reported in all subtypes,” the researchers wrote, referring to the bulbar muscles of the head and neck.

The children’s body mass index (BMI) trajectory was similar to growth curves for typically developing children, with little overall evidence of divergence across the first few years of Spinraza treatment. BMI is a proxy indicator of body fat, accounting for a person’s weight, height, and sex.

Still, individual variability was high, with some patients becoming underweight or overweight over three years of follow-up.

Growth failure, or a significantly poorer height for one’s age, also was observed in some patients, with a significant decrease in height-for-age percentiles seen in SMA type 2 patients over time.

Dietary intake was evaluated through interviews, with patients or their caregivers called on three random days and asked about the patient’s food consumption in the last 24 hours. The first of these interviews was conducted a mean of 1.6 years after starting on Spinraza.

Saturated fats and added sugars consumed at above recommended levels

Protein intake,”well documented to influence development of muscle mass,” was below the recommended level for 8% of the children given their age and weight. Excluding underweight patients and those requiring nutritional interventions, 86% of the group consumed higher than recommended amounts of saturated fats, and 38% consumed more than the recommended amount of added sugars.

“Added refined sugars provide energy but does not contribute with other nutrients,” the researchers wrote. “Restricted intake of added sugars is important to ensure adequate intake of protein, micronutrients, and dietary fiber.”

Indeed, 58% of these young patients consumed less than the recommended average of dietary fiber, which is important for promoting gastrointestinal health and preventing constipation.

Despite the common use of dietary supplements, 15% to 77% of patients were below recommended values for various vitamins and minerals.

Iron was the micronutrient that most patients (around 80%) consumed at levels below the recommended intake, with 17.5% found to be iron deficient in blood tests. Iron deficiency was more frequent with SMA type 2 (25%) than SMA type 3 (10%) in this study. But across types it was more frequent than is customary, with previous reports showing iron deficiency affecting about 8.2% of children in the general population.

More than a third of patients (37.5%) had suboptimal blood levels of vitamin D, a rate again higher than that reported in the general population.

“Despite the use of dietary supplements, 15-77% [of patients] had intakes below recommendations for vitamin A, vitamin D, thiamine, niacin, folate, calcium, iron, magnesium, potassium, zinc, selenium, and iodine,” the study noted.

Fatigue during meals noted as a common feeding difficulty

A questionnaire also found that “some level of feeding difficulties persist in a significant proportion of children and adolescents with SMA II and SMA III receiving [Spinraza],” the researchers wrote.

Difficulties included issues such as fatigue during meals leading to prolonged feeding times, and problems with varying food textures or using the hands or arms to eat. Besides fatigue, “difficulties with chewing various food textures were also a frequent issue and more prevalent than swallowing concerns,” they added.

As expected, feeding difficulties were more prevalent among those with type 2 disease (85%) than those with SMA type 3 (45%). These issues also significantly associated with a poorer protein intake.

Findings support the need for SMA clinical practice to place an “increased focus on assessment of dietary intake … to provide individualized dietary advice to increase overall diet quality,” the researchers wrote.

“Attention in clinical care should be on prevention and treatment of nutritional deficits with emphasis on iron and vitamin D status and adequate protein intake in children and adolescents with feeding difficulties,” they concluded.