Zolgensma’s Arrival Adds Urgency to SMA Newborn Screening Efforts in US, Europe

Written by |

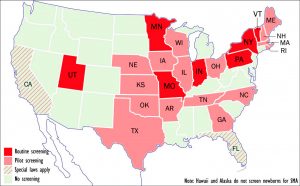

ewborn screening programs for SMA or plan to implement such programs. (Graphic by Armando Portela)

[Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a series of articles on Zolgensma and treatments for SMA, the issues they raise, and possible discoveries to come, all drawn from recent interviews with neurologists and researchers involved in this work. Others in this series can be found here.

SMA News Today is also interested in speaking with families of children treated with Zolgensma in its approved form, using intravenous injection, to share their experiences and opinions with our readers. If you or those you know are open to this interview, please contact us at [email protected]]

Recent approval of a gene therapy, Zolgensma, for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) — joining Spinraza (nusinersen), which has been on the market since 2016 — has injected new urgency into global efforts to screen all newborn babies for the disease.

“SMA should be part of every newborn screening list in the U.S. and across the world,” Vincent Carson, MD, a neurologist at the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, told SMA News Today by phone. “We need to speed that up, because now we have treatments available, and time is of the essence when it comes to preserving motor neuron function.”

Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi), developed by Novartis subsidiary AveXis, won approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 24 to treat all types of SMA in children younger than 2 years old.

Called a one-time treatment, its retail price of $2.1 million, makes it the world’s most expensive drug. Yet over a 10-year period, it’s half the price of Biogen’s Spinraza, which costs $750,000 the first year and $375,000 every year thereafter.

Zolgensma’s approval came four days after the publication of an article outlining “essential steps” toward newborn screening for rare diseases in the journal JAMA Neurology.

Five of the article’s 13 authors represent the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), which convened the review — including Rodney Howell, MD, chair emeritus of the pediatric department at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine.

“Newborn screening is one of the most important and impactful public health programs in the United States,” Howell, who also chairs MDA’s board, said in a press release. “Since its inception, this program has saved and improved the lives of thousands of children. Its continued expansion … will benefit many more families by enabling … the care their children need from day one.”

None of the three neuromuscular diseases discussed in the article — SMA, Pompe disease, or Duchenne muscular dystrophy — originally met the criteria for inclusion on the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) because effective treatments simply weren’t available at the time.

Pompe was added to the RUSP in 2015, and last year, the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children — created by Congress to promote a uniform national panel of diseases — recommended SMA as well. At present, the RUSP list includes 35 core and 26 secondary conditions.

7 states test for SMA

Yet, as the article points out, “it often takes years for RUSP-approved diseases to be adopted by all states,” and the newborn screening pilot study program is “a fragmented system.”

“Many state health departments do not consider research to be part of their mission or are prohibited from conducting certain kinds of research,” it continues, arguing for “a national infrastructure to conduct population-based screening on a research basis.”

Testing newborns for a deletion in exon 7 in the SMN1 gene could prevent the “need for mechanical ventilation” within the first year of life, or the death, of 48 of the roughly 4 million U.S. babies born each year, according to a March 2018 government report.

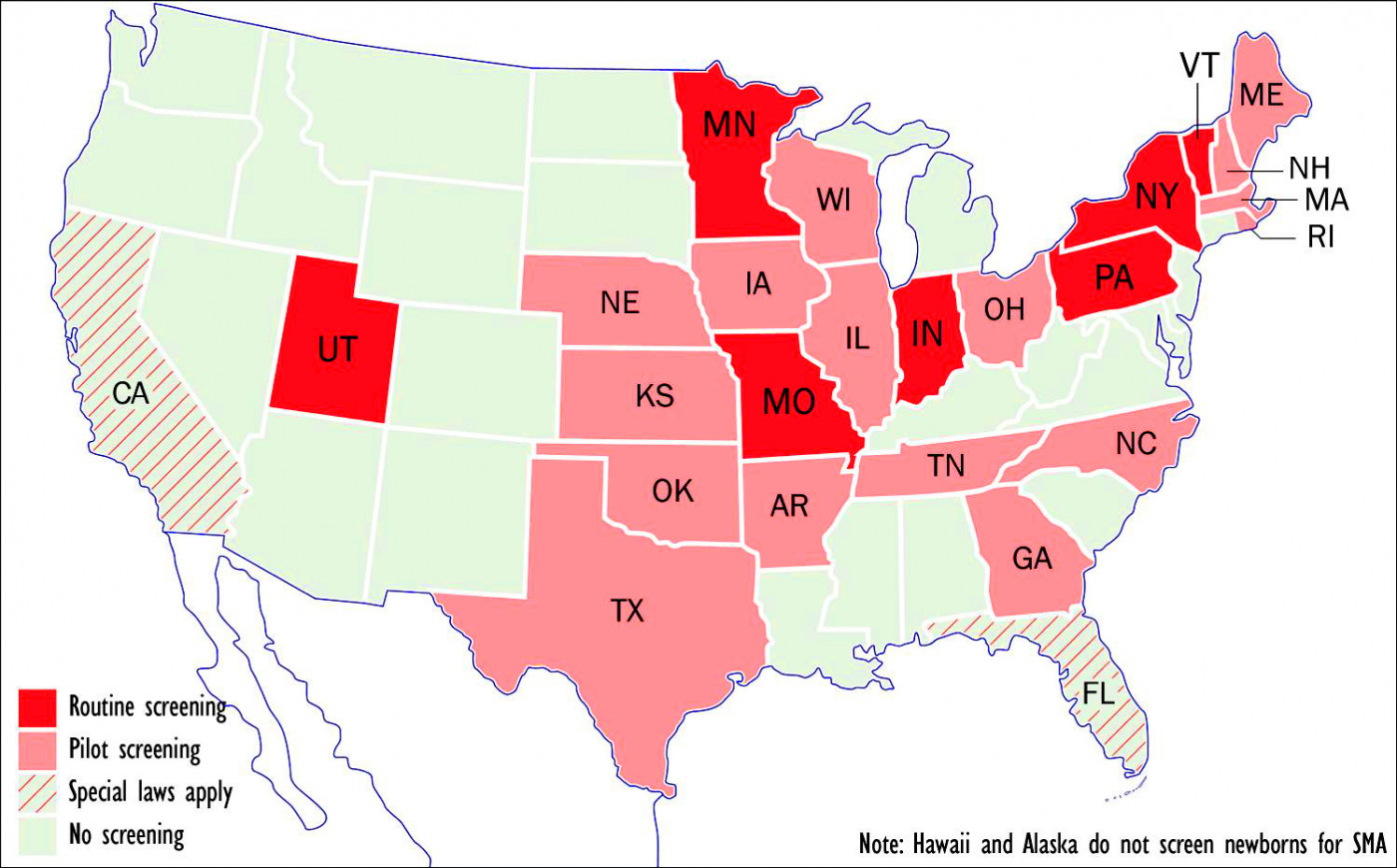

At present, seven states — Indiana, Missouri, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Vermont — routinely screen newborns for SMA, according to the MDA, while 16 more have either passed laws requiring such screening or are in the process of doing so.

States that have begun or are considering pilot screening include Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin.

California — with 40 million residents, the nation’s most populous state — requires testing of a new disorder to begin within two years of its inclusion in the RUSP. Florida — whose 21.6 million inhabitants make it the third most populous state — requires the state’s Genetics and Newborn Screening Advisory Council to review new RUSP additions within one year. If the council favors implementation, the state must do so within 18 months.

Yet newborn screening efforts at the federal level are “woefully underfunded,” Kristin Stephenson, the MDA’s chief policy and community engagement officer, said in a phone interview. For fiscal 2019, Congress appropriated only $16.4 million for the Heritable Disorders program of the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA), and $16 million to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for its newborn screening programs.

A bill to increase both those appropriations passed a House committee in May, but is not yet supported by the full Congress.

The MDA, Stephenson said, is working with groups like the March of Dimes to “get more funding at the federal level,” and prodding states to begin screening newborns for diseases included on RUSP.

“The approval of Zolgensma provides a new and exciting opportunity to demonstrate again the importance of having every baby identified at birth who can benefit from treatment,” she said.

Ohio pilot program yields results

Carson, whose Amish-funded Special Clinic for Children was profiled by SMA News Today earlier this year, stressed that treatment benefits depend on detecting SMA in babies as early as possible.

“I really think that, in light of these new treatments — both Spinraza and Zolgensma — it’s important that SMA be added to the newborn screening lists both in the U.S. and abroad,” he said. “I’m lucky that here in Pennsylvania, SMA was added to newborn screening this year.”

Neurologist Jerry Mendell, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, is a strong proponent of newborn screening for the disease.

“In Ohio, we have newborn screening now as a pilot project. We’ve already had two patients from that program and both were treated before 30 days [of age]. One is out for three months now and has no symptoms. The other is out to a month and has no symptoms,” said Mendell, principal investigator in the pivotal Phase 1 trial of Zolgensma (then known as AVXS-101) and its long-term extension, START (NCT03421977).

“Our intent from the very beginning was to show efficacy for type 1, and then it would be brought into more widespread use through newborn screening, because our most powerful results in the AVXS-101 trials were in newborns with minimal symptoms of SMA,” Mendell said. “Those are the patients that really returned basically to normal.”

The view from Europe

Throughout the 28-member European Union, where Zolgensma awaits a regulatory decision, newborn screening for SMA is limited to a few isolated pilot programs.

Kacper Rucinski, executive board member of the U.K.-based nonprofit group SMA Europe, last month took part in a three-day newborn screening workshop in Amsterdam organized by the European Neuromuscular Centre.

“The medical consensus was that … newborn screening for SMA should be introduced in Europe as soon as possible,” he said. “We need to come up with a standard [on] how newborn screening should be carried out, which methodology should be used, and how the patient should be informed in case of a positive result.”

Several pilot projects are underway. These include one program in two Italian provinces that will screen about 65,000 newborns a year, and another in the French-speaking region of Belgium that has already identified three or four babies with SMA out of around 30,000 screened.

Spain is about to start an SMA newborn screening program in Barcelona, Rucinski said.

“The EU has very limited powers regarding healthcare,” he said, adding that in his native Poland, a program aimed at screening 60,000 babies a year in Warsaw may begin in October.

Rucinski said SMA affects about 1 in 7,000 babies, though incidence varies from one country to another. On average, he said, screening costs 2 to 4 euros ($2.25 to $4.50) per test, which translates into about €30,000 (about $33,800) to detect a single case of SMA.

“We as a patient organization,” Rucinski said, “definitely think it’s worth doing.”