COVID-19 Infection Turns Severe, Deadly in SMA Type 1 Child

Written by |

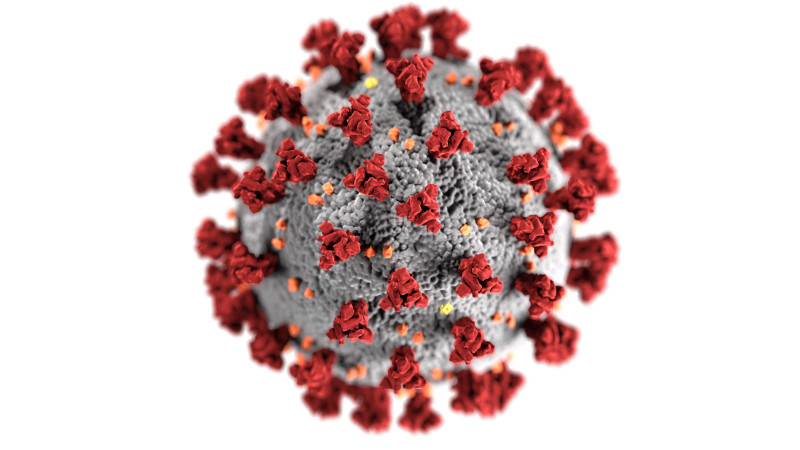

CDC/Unsplash

A hospitalized 3-year-old with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 1 died after being infected by the virus that causes COVID-19 and having a widespread inflammatory response — unusual in infected children — known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome, a case report found.

This girl’s case “highlights the importance of close surveillance, the use of protective measures during hospital visits, early testing, and diagnosis of COVID-19 in children with neurological disorders,” its scientists wrote. “Comorbidities [like SMA] in children pose a higher risk for serious COVID-19 disease.”

The report, “COVID-19 infection in spinal muscular atrophy associated with multisystem inflammatory syndrome,” was published in Case Reports in Pediatrics.

COVID-19 in children is usually mild, with some showing no symptoms. But those with certain underlying conditions, such as a rare and neurological disease like SMA, are thought to be more likely to develop severe COVID-19 symptoms.

One rare complication of COVID-19 in children is multisystem inflammatory syndrome, a serious condition that leads to fever and widespread inflammation affecting two or more body organs, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, and gut. A characteristic of this syndrome is a so-called cytokine storm, during which inflammatory cytokines (signaling molecules that help to regulate the immune response) are produced at much higher levels than usual.

Researchers in Saudi Arabia reported the case of a child with SMA type 1, who developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19.

The girl had been under the hospital’s care since age 1, due to recurrent lower airway system infections as a result of the repetitive aspiration that can mark SMA type 1, a severe form of this neuromuscular disease. She was dependent on artificial ventilation to breathe and fed using a gastrostomy tube.

Her clinical condition was stable until she began to have spikes of fever, along with a fast heart rate (tachycardia), abdominal bloating, and vomiting. Her airway secretions also increased and she showed intolerance to feeding.

While her lungs were clear on an X-ray, an airway secretion culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa — a bacteria that often causes lung infections. The girl was started on antibiotics, but her abdominal bloating and vomiting worsened.

Blood tests revealed higher-than-normal levels of C-reactive protein (a protein made by the liver) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (a measure of how quickly red blood cells settle in a test tube), both indicators of inflammation.

A first test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus causing COVID-19, came back negative. But due to her persistent fever and gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms, doctors still suspected infection. They started the girl on oseltamivir (an antiviral), oral dexamethasone (a corticosteroid), and intravenous immunoglobulin (an antibody), following Saudi Arabia’s guidelines for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Still, her condition worsened: levels of inflammation markers rose and she showed “an altered level of consciousness,” meaning she was not as awake, alert, or able to understand or react as previously. She also developed septic shock (very low blood pressure following an infection), with acute kidney and multiple organ failure.

Contact tracing found COVID-19 infection in family members who had recently visited the child at the hospital. A second SARS-CoV-2 test was given, and returned positive.

Additional treatments were started, including Actemra (tocilizumab), marketed as RoActemra in some countries, an antibody that blocks the binding of the cytokine interleukin-6 to its receptor on cells and is used to try and dampen a cytokine storm.

She continued to decline, however, and died.

This case indicates, the scientist wrote, “that children with SMA type 1 may belong to a high-risk group for COVID-19.”

As such, the “high morbidity and potential mortality” that can follow infection “should be drivers for heightened surveillance, and stringent personal protective measures and social distancing should be adopted when parents and families visit children [who are] hospitalized,” they concluded.