SMA Severity Linked to Greater Declines in Respiratory Muscle Strength

Written by |

Respiratory muscle strength is more severely affected in people with earlier-onset forms of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), but it generally declines over time across SMA types 1 to 3, according to data from a population-based natural history study.

One of the measures of respiratory strength, peak expiratory flow, was found to decline steadily over time in most types, highlighting its potential to assess treatment efficacy over the long term and in clinical trials, the researchers noted.

The study, “Natural history of respiratory muscle strength in spinal muscular atrophy: a prospective national cohort study,” was published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases.

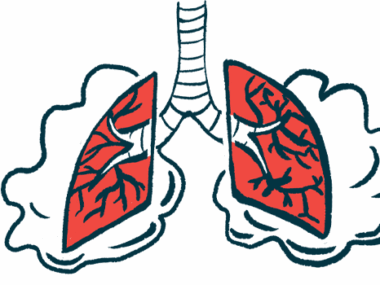

SMA is characterized by the progressive loss of motor neurons, the specialized nerve cells that control voluntary movement, resulting in muscle weakness and wasting. This affects not only muscles involved in motor function, but also those supporting the chest wall and breathing, particularly exhalation or expiration.

“Respiratory muscle weakness results in impaired cough, recurrent respiratory tract infections and eventually can cause respiratory failure,” the researchers wrote.

As such, breathing complications are the main cause of death in SMA, particularly in more severe SMA types.

However, how SMA and its different types affect muscle respiratory strength over time remains unclear. In addition, tests of respiratory muscle strength may detect breathing problems earlier than the more frequently used measures of expiratory lung function.

“Improved insights into the natural history of respiratory muscle strength could guide therapeutic management, improve timing of supportive care, and facilitate its use as an outcome measure for longer-term follow-up of patients or treatment efficacy assessments,” the researchers wrote.

With this is mind, a team of researchers at Utrecht University, in the Netherlands, analyzed respiratory muscle strength and how it changes over time in 80 children and adults (52 females and 28 males) with SMA types 1, 2, and 3 before they entered any clinical trial or received disease-specific treatment.

Most (67.5%) included patients who had been diagnosed with SMA type 2 (32 with type 2a and 22 with type 2b), while 20 (25%) had type 3 (16 with type 3a and four with type 3b), and six (7.5%) had type 1c.

SMA type 1, with an onset during infancy, is the most common and second most severe disease type, while types 2 and 3 are later-onset forms characterized by milder severity, particularly type 3. Each type can be classified into three subgroups (a, b, and c) with increasing age of onset, with subtype a being the most severe.

A total of 2,172 measurements of respiratory muscle function were analyzed in the patients, who ranged from 4.1 to 66.6 years of age. These non-invasive measures included maximal expiratory and inspiratory pressure (PEmax and PImax), sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP), peak expiratory flow (PEF), and peak cough flow.

PEmax and PEF are different measures of expiratory muscle strength, while PImax and SNIP reflect inspiratory, or inhaling, muscle strength. Peak cough flow, or the maximum air flow generated during a cough, is used to assess coughing abilities and strength.

This analysis was part of a larger prospective natural history study, of which lung function findings were previously reported.

Results showed that SMA patients, across all groups, had generally lower-than-normal respiratory muscle strength, according to all measures. This respiratory muscle weakness was more pronounced among those with more severe forms of the disease.

Type 1c patients showed no improvements in expiratory, inspiratory, and cough strength with increasing age, while improvements around adolescence or adulthood, followed by declines, were generally observed for the other groups.

Expiratory muscle strength, as assessed with PEF, showed a steady decline of 1%–2% a year across SMA types, suggesting that it could be used to monitor disease progression in all SMA patients.

Given that patients with more severe disease showed lower PEF values from the start, PEF dropped below normal during early childhood in types 1c–2, and during adolescence in type 3a.

Also, the PEmax/PImax ratio was lower than 1 throughout life in all SMA types, “indicating that expiratory muscles were most affected,” the researchers wrote.

“Interestingly, PEmax was low in patients with SMA type 3a from early ages on, whilst we have previously shown that lung volumes in these patients remain normal at least until (early) adulthood,” the team wrote.

These results suggest PEmax as a “sensitive screening parameter to detect respiratory muscle weakness in SMA patients,” the researchers added.

All but SMA type 3b patients had a lower-than-normal cough strength. Those with types 2a, 2b, and 3a showed values reflective of vulnerability to respiratory failure during otherwise non-severe lung infections, and type 1c patients showed even lower values, indicative of ineffective coughing and secretion clearance.

These findings highlight that “there are clear differences in respiratory muscle strength and its progressive decline between SMA types,” with the more severe types showing a greater impact, the researchers wrote.

Also, “PEF is among the most suitable measures to be used for the longer-term follow up of patients and treatment efficacy assessments,” and this natural history data may serve as a reference for such long-term assessments, the team concluded.