Newborn Screening for SMA Key as ‘Every Day Matters,’ Says Mom of Boy with Type 1

Written by |

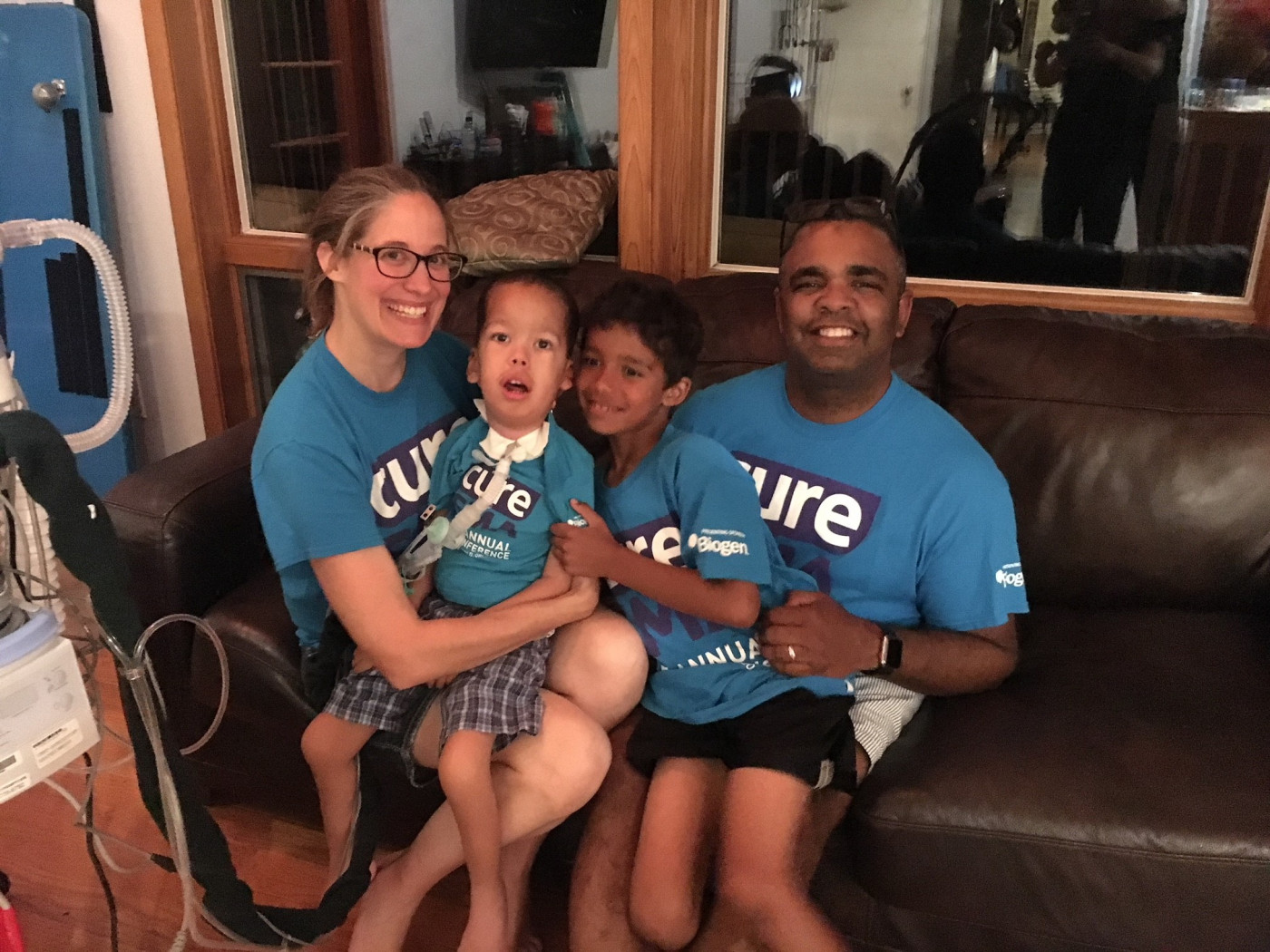

The Cardenas family. (Photo courtesy of Megan Cardenas)

When Megan Cardenas and her husband brought their 10-day-old son, Derek, to be screened for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the doctor told them their baby was simply lazy.

The infant might not be meeting early milestones, but he could roll over when placed on his side — something babies with SMA don’t do, the physician said in that June 2015 meeting.

Cardenas and her husband, who already knew they both were carriers for the genetic mutation that causes SMA, had their doubts. Still, the doctor was 100 percent sure Derek did not have the disease, and did not need to undergo genetic testing.

But over the next seven days, Derek changed. He couldn’t hold his head up. He stopped moving his legs. At 17 days old, his mother said, Derek was diagnosed with the most severe case of SMA type 1 his doctor had ever seen.

“When Derek was born, that was the typical story,” Cardenas told SMA News Today in a phone interview from the hospital where her son was receiving care for an infection. Like other parents, the couple “knew things were not quite right, they went to their doctor.” Tests were done, but not genetic testing. Not newborn testing.

Ask questions and share your knowledge of SMA in our forums.

SMA “was not something that they found until much farther down the line, when [the child’s muscles] are really, really atrophied,” she said.

After two nights of scouring the internet for information about SMA, Derek’s parents managed to enroll their 19-day-old son in a clinical trial at the SMA Research Center at Columbia University. Cardenas declined to discuss details of that trial or details of Derek’s treatment. Rather, she said only that Derek, now 3, is able to attend preschool and, with the support of his parents and caretakers, to do yoga.

Cardenas has become an active advocate for SMA and newborn screening for the disease.

She is telling Derek’s story to emphasize the importance of genetic newborn screening — a test given at a hospital to newborns to identify certain severe, but treatable, genetic diseases. These screens don’t uniformly include SMA, mainly because — until Spinraza was approved by the FDA in December 2016 — there was no treatment for the disease.

Alex Azar, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), added SMA to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) for newborns in July this year. Ultimately, though, the decision to test for SMA in the U.S. is made on a state-by-state basis. Currently, only seven states do so, with three others running a pilot program.

“Every day matters,” Cardenas said. “I wish we knew even sooner.”

Derek’s diagnosis allowed him to be enrolled in the study and begin getting multidisciplinary care — treatment that included physical and occupational therapy. If tested at birth, he might have begun such care earlier, possibly slowing the muscular weakness and atrophy caused by the loss of motor neurons.

“I knew at 20 weeks pregnant that Derek could have SMA and I still missed the boat,” Cardenas said. She and her husband underwent genetic testing, and knew they were carriers of a mutation that gave their child a 25 percent chance of developing SMA.

After his diagnosis, Derek’s parents went about their neighborhood — a complex of townhouses — asking people to participate in a national candle-lighting ceremony for SMA. To each neighbor, they handed small lights attached to a letter introducing Derek and explaining SMA, along with the importance of genetic newborn screening for both parents and newborns.

Cardenas estimates 90 percent of her neighbors took part. She still remembers being “teary-eyed” at the realization that she wasn’t alone, and that motivated her to continue spreading the word.

Moving Forward

Since then, Cardenas has regularly attended SMA conferences and Derek has been featured in educational videos. She raised funds to build a handicap-accessible playground in her community.

Every time she sees pregnant women on the street, Cardenas asks if they know the importance of genetic testing and newborn screening.

She said we take “every opportunity we get” to raise awareness.

Her goals are twofold.

First, she hopes to get all 50 states to mandate newborn screening for SMA.

Second, she hopes to educate both patients and healthcare providers about the importance of following SMA protocol and setting up a care team. The disease is rare, and many think if its detected and treated early, then that’s enough.

“But you’re not done. Those kids still need that multidisciplinary team watching them, making sure that they’re OK. Making sure they have the equipment,” she said. “Our kids change at a drop of a dime … When they’re sick everything goes out the window, and they need respiratory support and they need all these things.”

In September, Cardenas spent her birthday at a Cure SMA Summit. While she was there, her home state of New York announced that newborn screening for SMA would begin on Oct. 1. “It was the best birthday present,” she said.