Tau Protein May Be Marker of Long-term Response to Spinraza

Measuring tau levels in the spinal fluid is predictive, researchers suggest

Written by |

In people with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) who have been on long-term treatment with Spinraza (nusinersen), levels of the protein tau in the spinal fluid are decreased, a new study indicates.

The findings imply that measuring levels of tau might be a useful marker for predicting the response to treatment with Spinraza, researchers said.

“Our study shows that [tau] concentration is emerging as a reliable biomarker for monitoring the response of SMA patients to [Spinraza] treatment in the first 2-year period,” they wrote.

The study, “Total tau in cerebrospinal fluid detects treatment responders among spinal muscular atrophy types 1–3 patients treated with nusinersen,” was published in CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics.

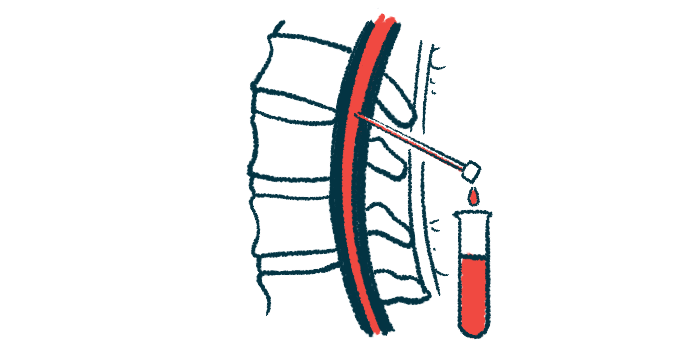

Spinraza was the first disease-modifying treatment for SMA to become widely available. It works by boosting levels of the SMN protein whose deficit causes SMA. Spinraza is administered every four months via intrathecal injection — an injection through the spinal cord into the liquid that surrounds the brain and spine, called the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Clinical trials have demonstrated that treatment with Spinraza can slow the progression of SMA, in some cases helping to improve muscle strength and motor function. Not everyone responds to treatment the same, however, and researchers are working to identify biomarkers that might help predict how individuals are likely to react to the therapy.

In this study, researchers in Croatia analyzed CSF samples collected from 26 people with SMA (13 with type 1, four with type 2, nine with type 3) who had been on treatment with Spinraza for varying lengths of time. In line with prior reports, results generally showed that most patients experienced improvements in motor function after some time on Spinraza.

Tau, NfL, and S100B

The scientists assessed levels of three potential biomarkers: tau, a marker of nerve fiber damage; neurofilament light chain (NfL), a marker of nerve cell damage; and S100B, a marker associated with inflammation in the nervous system.

Statistical analyses showed a significant negative correlation between tau levels and the duration of Spinraza treatment — showing that levels of tau in the CSF tended to be lower in patients who had been on Spinraza for longer.

Additional analyses showed that, in all patients, levels of tau were lower when the fourth dose of Spinraza was administered compared to levels when the therapy was initiated (baseline). Levels of tau also were generally lower than baseline for subsequent doses out to about two years on the therapy. But, after that, the relationship was less clear, possibly due to a fewer patients receiving treatment for more than two years.

The researchers concluded that tau “showed to be a reliable biological marker for monitoring the response to [Spinraza] therapy, especially in the first 18–24 months of therapy when it significantly decreased from baseline levels in all three SMA types, although in the longer term, this relationship was no longer maintained.”

“While the role of tau protein changes in mechanisms underlying motoneuron degeneration in SMA remains largely unknown … it appears that the measurement of [tau] in CSF is a valuable tool for monitoring the response to [Spinraza] in SMA patients,” they added.

Results showed no notable changes in levels of NfL or S100B associated with Spinraza treatment, however.

“Even though NfL reduction in CSF had been reported in a few studies of SMA patients on [Spinraza], NfL, in general, does not seem to represent a reliable biomarker to monitor the response of SMA patients to [Spinraza] treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The team noted that this study is limited by its small size and the lack of a clear comparator group.

Spinraza is sold by Biogen, which was not involved with this study.