18 States in US Screening Newborns for SMA as Efforts Continue for More, MDA Says

Written by |

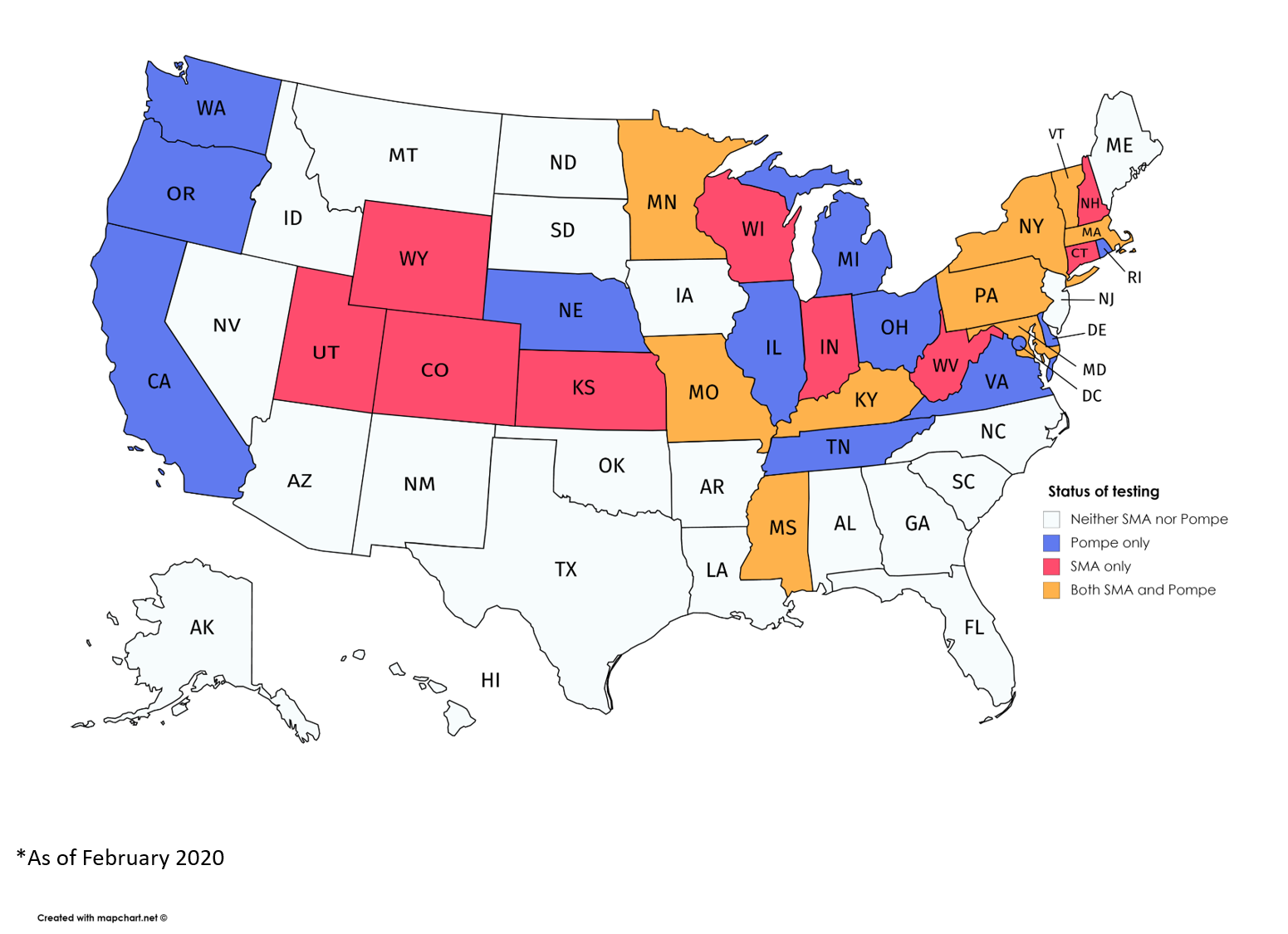

States conducting newborn screening for Pompe or SMA, and both diseases. (Courtesy of the MDA)

Eighteen states are now screening newborns for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), the most recent neuromuscular disease added to a list of serious genetic disorders that infants can be tested for shortly after birth, advocacy officers at the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) said.

California, the most populous state with about 39 million people, also is in the process of adding SMA to its list of diseases requiring screening. Kansas’ program became active on Feb. 1.

“The reason that we are such champions of newborn screening is that every baby has the opportunity to be identified at birth” and receive treatment “as quickly as possible,” Kristin Stephenson, an executive vice president and chief advocacy and care services officer for the MDA, said in an interview with SMA News Today. “It’s really a very effective vehicle.”

The 18 states with SMA screening programs in place are: Colorado, Connecticut, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Screening involves collecting a spot of blood from a newborn, and running it through tests that check, say, for protein or enzyme activity.

Pompe, a metabolic myopathy, is the only other disorder among the 40 distinct, and often rare, neuromuscular diseases covered by MDA on this federal list, known as the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP).

Not coincidentally, SMA and Pompe also are the only two of these 40 disorders with disease-modifying treatments — approved therapies that do more than ease a patient’s symptoms.

SMA was added to the RUSP in February 2018, a little more than a year after Spinraza, by Biogen, became its first disease-modifying treatment. Pompe joined the RUSP in June 2015; its sole modifying treatment to date, Lumizyme (by Sanofi Genzyme), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2010.

“It really turns on when therapies are available,” as a targeted treatment is a “necessary criteria” for a disease to be added to the RUSP, Stephenson said. “The speed at which newborn screening will be a viable option for diseases we cover directly correlates to the speed at which therapeutic development happens.”

Few question the importance of newborn screening in identifying a progressive and often life-threatening disease in the hours after birth, allowing a child to be treated before irreparable damage is done.

But the cost for states to screen each of the roughly 4 million babies born in the U.S. each year can be considerable. States, as a result, individually decide whether to screen for each of the 35 diseases listed on the RUSP, either by legislative action or a governor issuing an executive order.

Only California requires statewide screening to begin within two years of a disease coming on to the RUSP, said Brittany Johnson Hernandez, the MDA’s senior director of policy and advocacy.

Florida also is unusual in having some sort of required statewide implementation, but this demand only kicks in after state leaders agree to adopt a recommendation. As a result, Florida is only starting to put into place screening for Pompe.

Grants are available from the federal government, Stephenson said, but they’re “not always as robust as they need to be for implementation, and states have to find the funding for this.”

For this fiscal year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was allocated $17 million for its newborn screening program, Hernandez said, and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has $17.8 million to implement such screening nationwide.

Costs also vary greatly among states thinking of starting to screen babies for a given disease, depending on factors that can include new machinery, the capacity of existing screening labs, and the degree of additional staff training.

Other considerations for states are the “efficacy and availability of [approved] medications, and how many [healthcare] providers are available to treat children identified,” Stephenson said.

That’s where the MDA comes in to encourage state action, she said. Its MDA Care Centers has teams specialized in neuromuscular disease diagnosis, treatment, and management set up in 150 clinics across the U.S., with at least one such center in every state.

Getting a disease to be considered by members of the federal committee whose opinions determine the RUSP — called the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, or SACHDNC — is itself a rigorous and costly process.

Petitioners need to present proof of the effectiveness and availability of approved treatments, a validated laboratory test for a screen, and a study of the estimated population with the disease. The committee, after a review and independent evaluation, then makes recommendations to the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), who makes final decisions.

States are not bound to screen for any disease listed on the RUSP.

No new disorders are coming onto the RUSP right now, however, because the U.S. Senate failed to reauthorize the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act before it expired on Sept. 30, 2019. Allocated funding for screenings remains in place, but no work is being done by the federal committee that advises about diseases for the RUSP.

“We are working with partners across the patient advocacy space and researchers to try and move forward the authorization,” Hernandez said. “It’s really a matter of finding an appropriate vehicle [Senate bill] in the coming months.”

This ad-hoc coalition of patient groups also is petitioning Alex Azar, HHS secretary, to issue an executive order to restart the SACHDNC committee, allowing it to meet. The groups argue that he has the necessary statutory authority to do so.

“The program, though not authorized right now, still has funding appropriated for it, so ongoing work of national program is still active,” Stephenson said.