FAQs about Zolgensma

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Zolgensma in 2019 for the treatment of babies and toddlers up to age 2 with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene. This marked the first approval of a gene therapy for SMA and the second approval of a disease-modifying therapy for the disease.

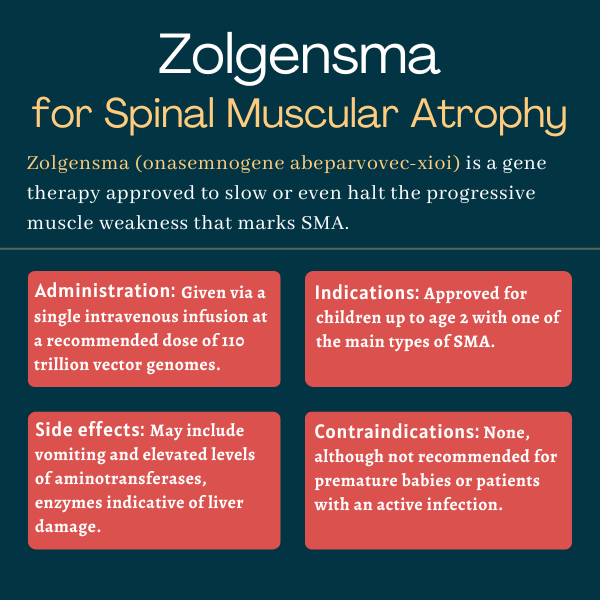

By delivering a healthy copy of the gene that’s mutated in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), Zolgensma can slow and even stop the progressive muscle weakness that marks the disease, enabling most patients to reach milestones that generally were not attained without treatment. In clinical trials, gains in motor function were seen as early as after one month of treatment, but some patients will take longer to experience benefits.

Based on data from four clinical trials, the most common side effects of Zolgensma were vomiting and elevated levels of liver enzymes, indicating possible liver injury. Other side effects that have been reported by patients since the gene therapy’s approval include fever, acute liver injury or failure, and clotting disorders such as thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels) and thrombotic microangiopathy (abnormal clotting in small blood vessels). There also have been reported increases in troponin-I protein levels, indicating potential damage to the heart muscle.

Zolgensma has been shown in trials to possibly be associated with liver damage that can ultimately result in serious liver failure and death. To prevent this potentially life-threatening side effect, patients who receive the gene therapy are also given corticosteroids for a month; however, they still should be regularly monitored for signs of liver damage. It is recommended that families and caregivers of children with spinal muscular atrophy who are preparing for Zolgensma treatment speak with their healthcare providers to know more about other potential complications.

Zolgensma has been mostly tested in infants and toddlers with spinal muscular atrophy, in whom it was deemed safe and able to improve or maintain motor function. A couple of trials also have enrolled adolescents as old as age 17 but the gene therapy has never been tested in adults, who tend to have milder forms of the disease. In the U.S., the therapy is only approved for children in the first two years of life.

Related Articles

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by